Notes

Torture At Bagram: What Difference Would Photos Make?

Below is a slightly distilled version of an entry I posted on March 24, 2005. It involves a lot of guesswork about torture meted out at America’s Bagram prison in Afghanistan. Over the past two days, there has been a lot of debate about the pros and cons of releasing photo documentation of the Bush Administration’s torture regime. Most of that debate, however, has taken place in the abstract.

My thought was to consider the issue in the context of a specific example, one in which basic facts and even scribbled diagrams exist, but to which a photographic record could, at least hypothetically, be added. If that was the case, I’m wondering if it shifts the debate at all in considering the pros and cons if the American people and/or American legislators and/or the Justice Department and/or the taxi driver’s family and/or the Afghanis could actually see what happened to this taxi driver.

Also, I’m thinking of the impact and significance of actually being able to see inside one or more installations beyond Abu Ghraib (particularly “black sights” that, up until now, have maintained an aura of invisibility — if the new batch of photos offered us a first look) to visibly appreciate that the torture regime did (does?) extend beyond that single location with its known actors.

If you’re interested in the original post with comment thread, click here.

*** ** ***

Over the past week, the media has been full of reports of prisoner abuse at Bagram prison in Afghanistan.

In an article and an accompanying multimedia report, NYT writer Tim Golden chronicles the plight of a frail 22 year old taxi driver named Dilawar. With the recent release of 2000 pages of Army documents concerning the prison, it was discovered that Dilawar was detained on December 5th, 2002 and died on December 10th. Besides detailing the treatment that lead to his death, the documents reveal a culture of violence at the facility involving torture, beatings and humiliation.

Among the Army documents are diagrammatic drawings. In his piece, Mr. Golden presents a number of these diagrams. This one, for example, outlines the way prisoners were placed in 9 foot by 5 foot cages, hooded and then chained to the ceiling.

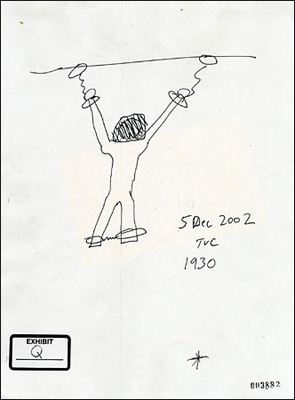

The image that really caught my attention, however, was a drawing sketched by Thomas V. Curtis, a Reserve M.P. sergeant, showing Dilawar in such circumstance. This drawing not only provides us an unusual glimpse into Dilawar’s plight, it offers a psychological window through which to consider Bagram’s culture of abuse.

Apparently, this drawing captures his first day under interrogation. (As I mentioned, he only lasted for five.)

According to the documents, new prisoners were often hooded, shackled and isolated for 24 to 48 hours. If a prisoner was judged to have broken the rules, he could be handcuffed to a door or ceiling for a half hour to an hour, or even longer. Records show that Dilawar had been shackled at the hands and feet almost the entire time he had been at Bagram. According to the autopsy, Dilawar died from heart failure caused by “blunt force injuries to the lower extremities.” Both legs had been thoroughly battered — akin to “having been run over by a bus.”

If there is one question that keeps coming up in abuse cases — such as those here and at Abu Ghraib — it is how a soldier can perpetrate this kind of treatment. Perhaps this image speaks to some of that mindset.

Here are a number of things I found curious:

In the drawing, Dilawar’s shoulders look somewhat muscular. In reality, he was just 5′ 9” and 122 pounds, and described as frail.Although hanging from the ceiling, the chains are slack. If anything, it looks like he is in a standing position.

He has no feet.

If Sergeant Curtis used the whole sheet of paper (which appears the case given the cross mark near the bottom and the placement of the log-in notations), it’s notable how small the drawing actually is.

Dilawar is drawn wearing a hood, but his head is outlined as fallen to one side.

So, what are we to make of this?

I have some some thoughts. As always, however, I’m as interested in yours.

In the drawing, there seems to be a tendency to minimize the duress. This might be see in the width of the chains relative to the wrists; the small size of the drawing relative to the paper size; and in the abbreviated ceiling line floating in space.

The slack in the chains and the absence of either tension or limpness in the body suggests a denial of the violence and its results. The absence of external walls and the inability to determine any ground line also makes the situation less “scalable” and thus more abstract.

I can think of a few reasons to “add muscle” to Dilawar. Just like the neocons need to build up the threat of minor dictators, these soldiers had a need to see the prisoners as larger than they were. This tendency makes even more sense considering that most of the detainees at Bagram had minor offenses at best, and were basically holdovers from those transferred to Guantanamo Bay.

Here are some thoughts on the lack of feet: a) If you don’t draw the feet, it looks less like he’s hanging. a.) His legs and feet were so beaten up, they were simply omitted. c) They don’t show up because of the angle.

The fact Sergeant Curtis drew Dilawar’s head beneath the hood might suggest some humanistic instinct. Perhaps Curtis was less involved in the beatings.

What’s your take?

(Revised: 5/24/05 8:45 am PST and 5/15/09 for clarity.)

(image 1 & 2: The Bagram File. May 20, 2005 in nytimes.com. image 3: Army sketch by Thomas V. Curtis, Army Reserve M.P. May 20, 2005 in the nytimes.com)

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus