Notes

The New Oil

by BNN contributor John Lucaites

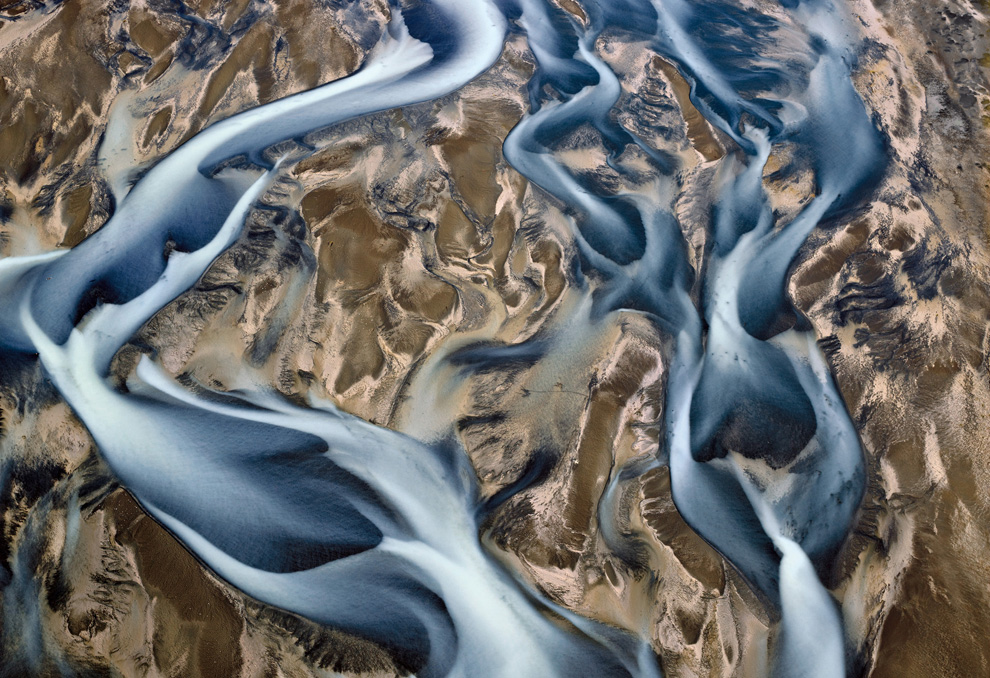

Oil, we are often told, is the lifeblood of late modern, industrialized civilization (here, here, and here) and certainly there is plenty of evidence that we behave as if we believe it. But as the photograph of Iceland’s Kolgrima River shot from somewhere in the heavens suggests, the real lifeblood of any civilization on earth is water. I say shot from the “heavens” because it is less realistic than William Ander’s iconic Earthrise, a clearly mechanically produced image that implicitly foregrounds the technology that enabled it.

Here the image has something of an abstract expressionistic quality to it that nevertheless underscores the naturalistic blending of land and waterways, a surface manifestation of an underlying essence accented by the soft contrast of the muted pastels. One can almost imagine the earth as a living entity, the blue veins throbbing in unison as they work to carry the nutrients necessary to bolster and sustain the ground. It is a beautiful and compelling—almost utopian—God’s eye view. 70% of the earth is covered by water, but 97% of that is found in oceans and seas, with another 2.4% in glaciers and polar ice caps. That leaves very little fresh water for all of its various needs, including most importantly consumption, sanitation, and agricultural production.

This has not yet proven to be a disastrous situation in the United States—despite some scares as the recent drought in the southeast—where the average resident consumes 100 gallons of water a day. But to put it in context, we need to note that in some places in the world the most indigent people subsist on 5 gallons of water a day—when they can get it. Nearly 50% of the people on earth do not have water piped into their homes, and in some developing countries women walk an average of 3.7 miles a day to get what they need. And the most sobering fact of all is reported by the Water Resources Group (sponsored by the World Bank Group and a number of global financial, industrial, and agribusiness concerns), which notes that by 2030 water demand will exceed supply by over 50% in some developing regions of the world effecting over 1.5 billion people.

And so, to return to earth from the heavens there is this image of a reservoir in China’s Yunnan Province:

The contrast between the two images could not be more stark. Here the earth is dried and cracked, its parts broken and fragmented rather than blended. There is nothing that approximates movement in the photograph; indeed, there are no signs of vitality at all. One of the often claimed effects of such desertification is a dangerous reduction in biodiversity, but here it is hard to imagine any biology at all. Of course, even the slightest accumulation of moisture might change that, resulting in a desert oasis, but the extreme close-up of the photograph locates the image in the here and now. It is a human’s eye view, and it underscores the immediacy and palpable effects of the threat.

Water, not oil, it would seem, is what is most essential to life on earth. One can only imagine what the world will be like in 2030 if we don’t come to terms with that sooner rather than later.

(photos: Hans Strand/National Geographic; Ariana Lindquist/Bloomberg. March 22, 2010 was World Water Day. The April issue of National Geographic features the importance of water to life on earth. Also, thanks to The Big Picture for calling my attention to the topic.)

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus