Notes

A Look Back at "Looking For Evidence": A Recent Interview with Eva Leitolf

Pond, Viersen, 2007 — A twenty-two-year-old man told the police in Viersen that on 10 July 2006 he had been verbally abused and physically assaulted by four young men on account of his skin colour. He said that he had succeeded in defending himself and getting away. The state security department of the Mönchengladbach police took charge of the investigation but was unable to identify any of the perpetrators. ©Eva Leitolf

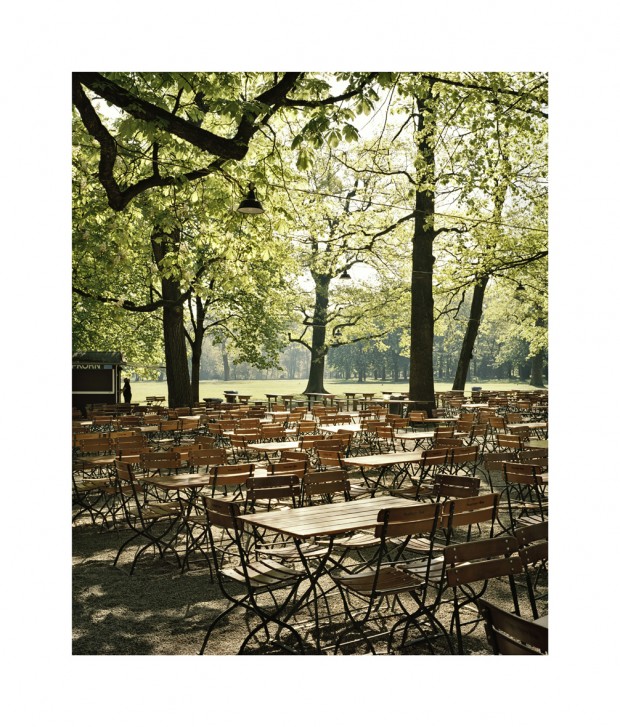

Hirschgarten, Munich, 2007

On 10 August 2000 the Green group on Munich city council organised a minibus tour of the city’s ‘centres of right-wing extremist activity’ for the press. The itinerary included the headquarters of a rightwing student fraternity, the offices of a right-wing intellectual magazine and the home of the leader of the DVU party. According to the press release, right-wing extremist structures in eastern Germany had been built and funded from Munich and Upper Bavaria. Hirschgarten was identified as a meeting place for right-wing extremists where many violent attacks had occurred. ©Eva Leitolf

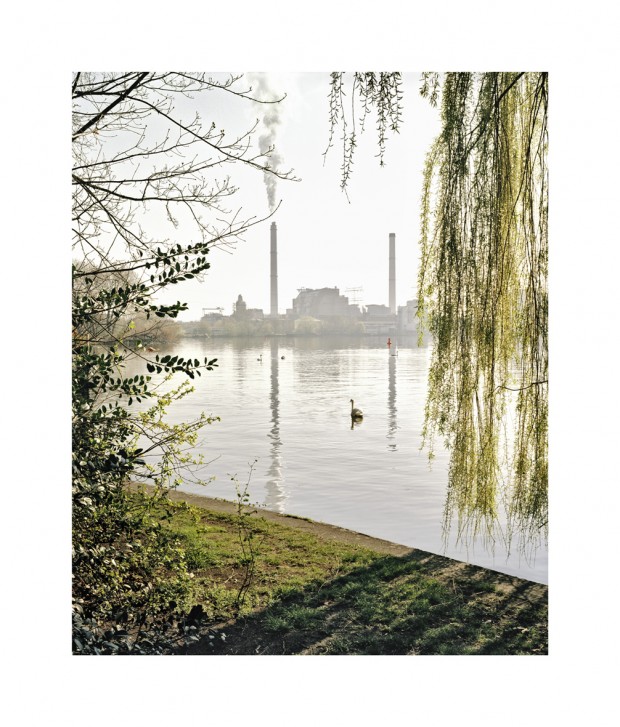

River Spree, Berlin Friedrichshain, 2007

During the night of 25-26 July 1994 a Polish building worker drowned in the River Spree in Berlin. After an argument with a group of young Germans, the forty-five-year-old man and his thirty-six-year-old countryman had been pushed into the water and prevented from swimming to the bank. It was claimed that the events had been triggered by the two Poles pestering two young women. Apoliceman reported having heard shouts of ‘Poles piss off’ and ‘Don’t let the Pole out [of the water]’. The court found no xenophobic motive, saying that the shouts may merely have referred factually to the nationality of the victims. In May 1995 four men aged between nineteen and twenty-five, and two girls aged sixteen and seventeen were found guilty of bodily harm followed by death and given custodial sentences (in some cases suspended) of up to four years. ©Eva Leitolf

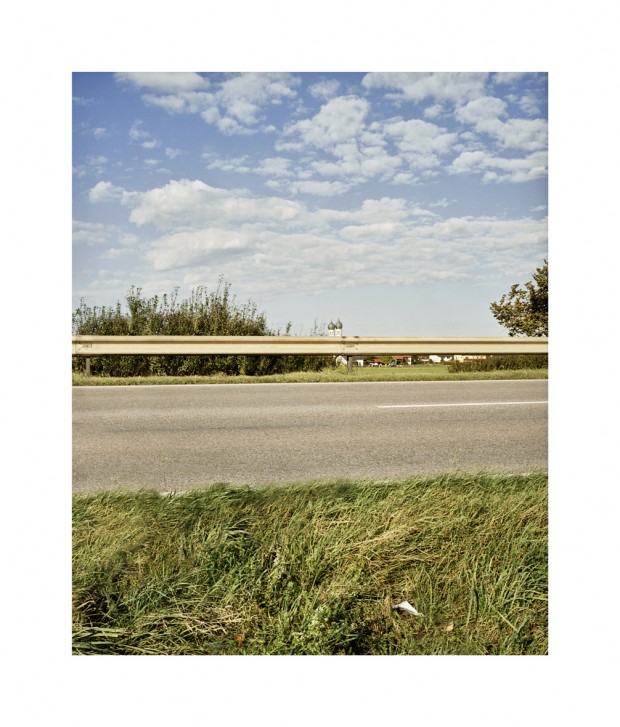

State road, Weihenlinden, 2007

On 16 May 1999 there was a serious road accident on state road 2078, where all five Turkish occupants of the car were killed. Two days later a driver discovered a poster at the scene of the accident bearing a swastika and the words ‘the moral of the story – dead Turks don’t bother us’. The poster was secured by the police and examined forensically, but the investigation remained inconclusive. ©Eva Leitolf

By the village pond, Pömmelte, 2007

The son of an Ethiopian man and a German woman who lived in a children’s home in Pömmelte was verbally abused in a bus by five juveniles on 9 January 2006. When the twelve-year-old got off the bus in Pömmelte, the group followed him several hundred metres through the village before maltreating him for more than an hour at the village pond. He was spat upon, beaten and kicked with army boots. The perpetrators forced him to lick their boots and trainers and to answer questions with ‘Yes, my Führer’. The ringleader threatened him with a gas pistol and throttled him, while another urinated on his head. He was subjected to a tirade of verbal abuse. The boy suffered thirty-four injuries, including craniocerebral trauma and a broken nose, and had to spend a week in hospital. The court found that the sixteen- to twenty-year-olds had sadistically tormented and gravely injured their victim for racist reasons, and sentenced the ringleader to three and a half years youth custody. Three other accused were given suspended sentences. In response to the crime the anti-fascist alliance in Schönebeck and Magdeburg called a demonstration in Schönebeck on 25 February 2006 under the slogan ‘Don’t look the other way, intervene!’ At the same time the Young National Democrats and other local right-wing groups organised a counter-demonstration entitled ‘Stop the media hate campaigns! They talk about Nazis but they mean all us Germans!’ ©Eva Leitolf

Lake Schwerin, near Berlin, 2006

A group of French and Italian teenagers – black and white – camping by the lake near Berlin were attacked on 1 August 2006 by a German youth throwing bottles. The attacker gave the Hitler salute and went on with two friends to Gross Köris, where he smashed a window of an Asian take-away. Following police investigations, the three suspects were charged with criminal damage, displaying banned symbols and attempted grievous bodily harm, as well as a robbery committed later. One of the perpetrators was sentenced to two years youth custody (suspended), another to one year and six months youth custody (suspended), while the third was cautioned.

Althaldensleben (‘Olln’), 2007

On 12 December 2006 six posters bearing the messages ‘All nonwhites to keep out!’ and ‘Keep Olln clean!’ were found posted in the district Althaldensleben. An investigation was initiated against persons unknown on suspicion of incitement to racial hatred and the results were passed to the Magdeburg state prosecutor at the beginning of 2007.

***************

Eva Leitolf’s “Looking For Evidence” is an incredibly beautiful photography book with outstanding reproductions. And just what is the subject matter that is so beautifully captured and portrayed? Grand scenic vistas? Natural scenic wonders?

They are essentially banal and vacant crime scenes- inconspicuous corners, streets, and crossings in Germany where racial assaults, beatings and confrontations had recently occurred. There is no telling evidence left to be examined, no remnants to suggest. It seems as if Eva Leitolf literally commanded these photographs to captivate and sustain our interest through sheer force of will. Her straight forward compositions are often bolstered by a vibrant color palette, but basically what she has pulled off is a conceptual tour de force- a visually entrancing one with an otherwise mundane sight unseen infamous only for something it cannot possibly portray.

Perhaps this is what is meant by a viable alternative to the current in your face tragedy journalism. And it is easy to understand why it is not exactly common practice- one doesn’t cover a news event well after the “decisive moment” has long left the building. But it is not entirely without precedent. Simon Norfolk and a small handful of other photographers have covered events after the fact in a somewhat similar fashion, and Joel Sternfeld’s “On This Site” covered much the same territory with the exact same technique back in ’96, but his subject matter was more varied and his photographs considerably more pedestrian. Many of Leitolf’s images however, manage to resonate profoundly even when one is completely unaware of their historic, and quite horrific, context.

If it wasn’t for the informative captions that accompany each of Leitolf’s photographs, one would remain oblivious to their true nature, and simply partake in their beauty. This sidelong exercise in photojournalism demanded further explanation, and fortunately, Ms. Leitolf was forthcoming:

SB: What first interested you in racial/immigration issues? When did you first think of integrating those concerns with your photography?

EL: Back in 1992, I was studying photography in Essen and needed to make a decision on the subject of my diploma project.

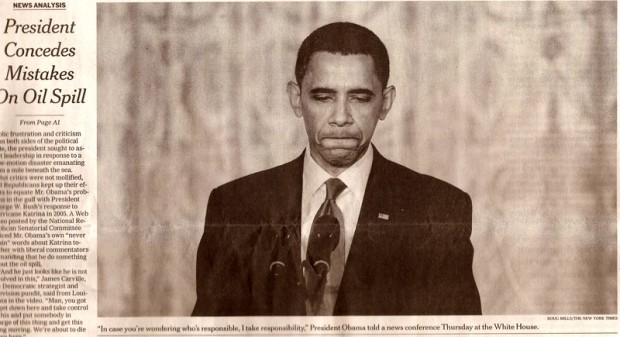

At that time numerous racist or xenophobically motivated crimes were committed in Germany and I was dissatisfied with the way most of the German news media dealt with it. It was the same picture everywhere: before the crimes occurred there was a massive use of xenophobic metaphors both in pictures and texts (“the boat is full” kind of thing), followed by cover photographs like the one of a seemingly helpless border patrol officer trying to keep a flood of immigrants out of the country (Der Spiegel titled this as “the helpless state”). After the arson attacks, and other racist crimes were committed throughout the country, “The Nazi Kids” made it to the magazine covers and TV news. In this scenario none of the rest of us, of the rest of society, had anything to do with it.

My interest in the subject was closely connected to an interest in how pictures work and, in a more general sense, how meaning is produced through connotation.

SB: How did you come up with the concept of photographing such scenes of violence (depicted in Looking For Evidence) well after the fact? Did you consider more traditional approaches? Were you aware of Joel Sternfield’s On This Site?

EL: German Images consists of two parts : an early part, from 1992 to 1994, and a recent part, from 2006 to 2008.

At the time I understood the early photographs as an attempt to look for what was there besides the Hitler-saluting skinheads. Going after the fact and to explore the locations beside was a direct reaction to my concerns with the simplistic narrative that was commonly put up by the German mainstream media.

Twelve years later I initially wanted to put a book together with this early work. It had been published in several anthologies but has never found its right form for me. During this process I looked back at several issues around the work that still seemed interesting to explore: the relation of photography and text, the tension between what can be seen, and what is left to the imagination, the way German society deals with racist and xenophobic violence today.

I was aware of Sternfield’s On This Site but don´t relate to it too much. I think Sternfeld is rather trying to create a photographic memorial for crime victims than to talk structurally about of how societies deal with crimes, perpetrators or victims. I feel far more influenced by others, for example by Eugene Atget´s sense for the absence, Robert del Tredici´s thorough research practices and Allan Sekula´s theories – Sekula was one of my teachers at Cal Arts in the mid nineties.

SB: One can’t get over just how beautiful these photographs are! Were you ever worried that you would not be able to come up with a visually arresting image at a particular location?

EL: During the two years I was working on the new part of German Images, I traveled to a tremendous number of places that could have been part of the final project. The fact is that racist violence is reported almost everywhere in Germany, and you can find thousands of relevant incidents, both major and minor. So to answer your question more directly: I did not take pictures of all the places I went to.

SB: What has been the overall reception to this work- from the “art world,” news media, social organizations and activists, and last and not least, the immigrant community and those directly affected?

EL: I can´t describe an overall reception. The work was shown in art venues like the Pinakothek der Moderne in München or the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum in St. Louis, in the US. It was well received by German art critics, got published in the Süddeutsche Zeitung Magazin, but got nasty comments in letters to the editors. There were invitations by social or political organizations to show the work which I didn´t accept, because I had the feeling that the work would become exploited in a way I didn´t feel comfortable with. A big surprise to me were the many positive reactions I got via email from all over the world by people with very different backgrounds who came across German Images on photo blogs or on my website.

SB: I’ve always been under the impression that Germany has rather comprehensive laws governing hate crimes/speech, especially those involving their Nazi past. And yet I couldn’t help notice how many of the crimes reflected in your work were either unsolved or rather lightly punished- which seems to almost condone, or at least tolerate this behavior. Is this common with respect to other areas of German law, or is this more reflective of the will and attitude of Germans in certain (geographical) areas when it comes to race/immigration?

EL: There is probably no simple answer to that. The biggest issue in here doesn’t seem to be the legislature. As you said, there are comprehensive laws.

For example, in Rostock-Lichtenhagen, where I went in 1993, the neighbors had watched arson attacks on a housing centre for immigrants and the adjacent Vietnamese homes a year earlier, and applauded them. So it came as no surprise that I was told things like “the way our youngsters did it might not have been the best one, but somebody needed to act and do something about the immigrants”. There are comprehensive theories that an escalation in Rostock was politically intended or at least welcomed in order to speed up and influence the debate on German asylum laws at the beginning of the nineties.

While doing research twelve years later I personally encountered very many concerned and helpful people both within the police forces as well as the prosecution and judicial system. Nevertheless there seem to be problems within these fields as a number of cases suggest.

SB: Would you consider using a similar approach for other projects? Or were you attracted to this project, at least in part, because you could approach it in such a “nontraditional” manner? What’s in the immediate future?

EL: I am as interested in the subject matter of my projects as I am interested by the specific approaches that develop in the process of dealing with them. I can’t think separately of one and the other.

For the past two years I have been looking at the European Union´s Schengen borders, their effects on migration and European societies. The working title for this project is Postcards from Europe and it is in some ways related to Looking for Evidence.

More Stan Banos at reciprocity failure and expiration notice.

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus