Notes

Racism as Style: The Return of Blackface

It’s becoming increasingly difficult for me to overlook the tremendously casual manner in which fashion photographs repeat the ghoulish visual history of racism as style. The unarguable popularity of the work of photographers like Viviane Sassen, or the unblinking publication of photographs of models in blackface by Greg Kadel or Steven Klein would seem to underscore the resurgent appetite for an imagery that rehearses some of the most profoundly derogatory aspects of orientalist and racist visual history. The issue is further complicated by the fact that this kind of imagery regurgitates old pejorative sexist tropes as well as racist ones. In a sense, sexism overlays racism in this kind of imagery to produce not incrementally but exponentially worse results.

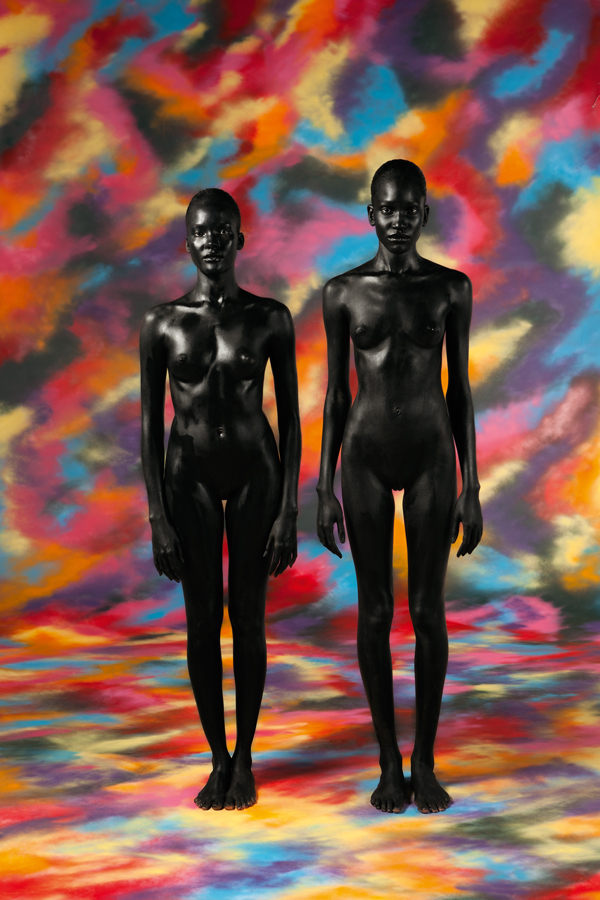

On Tuesday of this week, the British creative arts website It’s Nice That published a feature on a photo-shoot by French multi-disciplinary studio Akatre entitled Tropical. The images consist of two young naked women painted entirely (and unrecognizably) black, stood in front of a brightly patterned tropically-themed seamless backdrop, or reflected in the smooth dark mirrored surface of a black table. In the written part of the feature, the writer explains of the makers of these images that:

“Their most recent shoot for OOB magazine does absolutely nothing to dissuade us from our conviction that these guys are extraordinarily talented, showcasing an acute understanding of texture, colour, composition and just plain old good photography in a series of ten striking images. It’s testament to that talent that these images so readily stand out against a constant stream of naked bodies and bright colours that we’re subjected to each day online. But Akatre just aren’t the kind of guys to produce anything run-of-the-mill.”

It would be tempting to infer from this statement that there is a problematic lack of imagery of nude black female bodies in the “constant stream of naked bodies and bright colours that we’re subjected to each day online.” Such a lack is in fact indicative of the deep racial divisions in the employment of black female models in the fashion industry. However, this feature does not seem to concern itself with the very inequalities that its imagery exacerbates. It is also tempting to wonder whether a similar lack of imagery of nude male figures (black or otherwise) would be construed as a problem to which ‘talented’ image makers could respond, perhaps in the way that Katy Grannan’s portraits in the book Model American address themselves to the complexities of nude portraiture considered along the lines of divisions of gender and race. However it seems to me that what we are supposed to celebrate here is the striking quality of the images themselves, quite apart from the determinist politics that they so crudely represent.

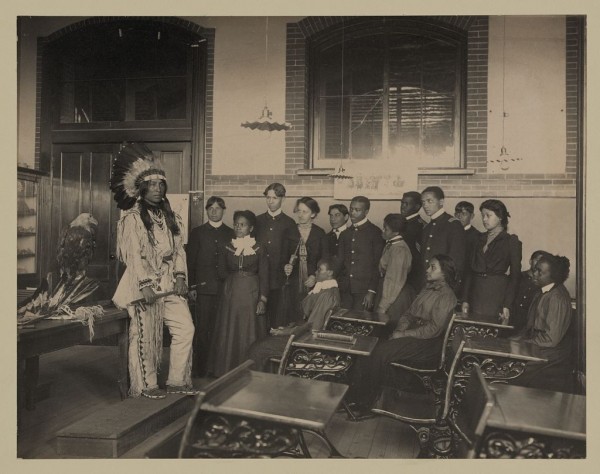

Frances Benjamin Johnston, “Louis Firetail, Sioux, Crow Creek, Wearing Tribal Clothing in American History Class,” Hampton Institute, Virginia, c1899-1900

What is most troubling about the publication of these undeniably striking images is their casual dissociation from anything resembling the problematic history of racism, subjection, violence or objectification. That they should have been produced in contemporary France, at a time when that nation’s black female Justice Minister is accused of having ‘found her banana’ for standing up to racial slurs from far-right politicians equally seems to add little useful context. In fact one can only assume from this celebration of these images that more work of a similar nature is required, and is to be encouraged.

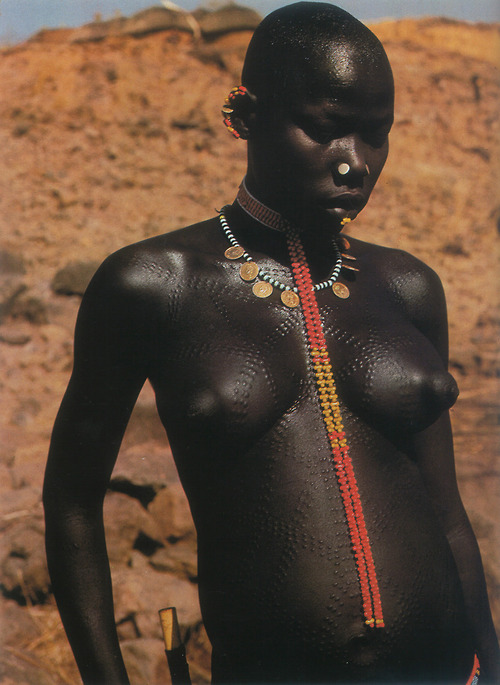

Leni Riefenstahl, from “The Last of the Nuba”

Prejudice depends upon, produces and reconfirms essentialist stereotypes about entire groups of people, and it does so in order to facilitate their marginalization, to enhance their subjection, and ultimately to legitimate violence against members of a class it seeks to designate as ‘suspect’. That violence can as easily be economic as political, as easily verbal or visual as physical, and it can be encouraged by the uncritical celebration of racist imagery when such imagery is celebrated as pure style, divorced from a history to which it owes its very existence.

Viviane Sassen, “Spring of the Nile” from “Flamboya” (September 2009)

To my mind it is very hard indeed to recognise any substantive distinction between these Akatre images and the images I cited in an earlier post on this topic, a number of which are reproduced here. Each image produces as its subject a kind of blackness that is ostensibly elemental, organic, rich in spiritual and physical vitality, and yet unreconstructed, nude, or found in a state of savage grace. Such imagery reconfirms white western colonial superiority by pretending to value highly a subject it designates as primitive, and by celebrating that primitive quality with a technology that clearly underscores implicit western superiority. This is a neat trick, but at heart also a deeply cynical ploy.

Jean-Paul Goude, Naomi Campbell in “Wild Things,” from Harpers Bazaar, 2009

Greg Kadel, Constance Jablonski from “Número” (October, 2010)

I would argue that it should be far more problematic to produce imagery of this kind, not in spite of the undeniable progress toward equality of race and gender that we have witnessed in recent decades but because of it. Those that support the widespread circulation of this blackface/orientalist imagery should be called into question, not from the perspective of a marginal struggle for some particular interest group but on the basis of an interest in the quality of our collective social and cultural space.

Our capacity to anticipate, approximate or empathise with those who are different from ourselves depends upon us viewing the prejudices from which they suffer as problems for us all. Such images cater to an instinct to belittle, to depersonalise, to fetishise the black feminine form as animalistic and as ‘other’, and consequently they encourage a way of seeing that is antithetical to common decency. As I said, it’s becoming increasing hard for me to overlook how casually this sort of work is made, circulated and celebrated.

— Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa

(adapted from the Tumblr blog, The Great Leap Sideways)

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus