Notes

James Whitlow Delano – Fifth Dispatch: Slash Cameroon’s Rainforest and Lose Ancestor’s Souls

In this longread and photojournal for BagNews Originals, photographer James Whitlow Delano details the impact of multinational logging and palm oil operations on the people and rainforest of Cameroon. In previous posts in the series, he details the devastation of the rainforest in Malaysia and Indonesia and the impact on indigenous tribes resulting largely from the corporate cultivation of palm oil. In Suriname, he documents the social and environmental effect of intensive international mining operations.

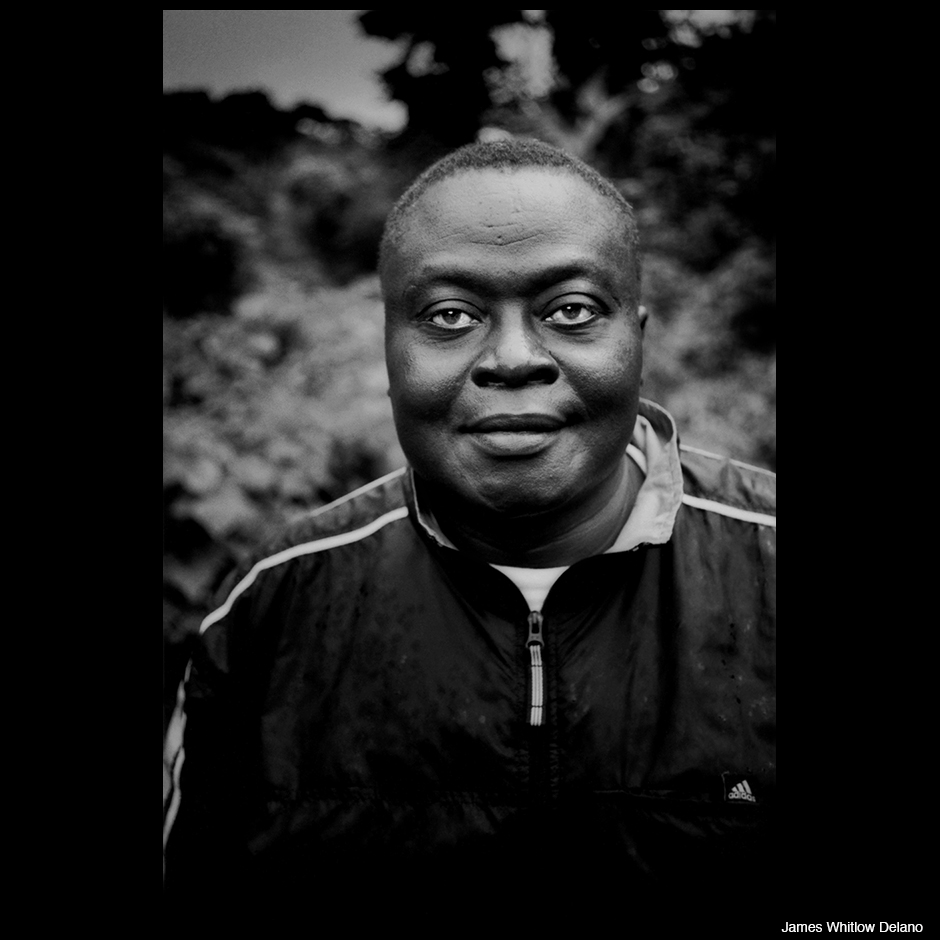

Talangaye, Cameroon. Cameroonian activist Christopher Achobang, who is working to prevent the proposed Herakles Farms logging and oil-palm concession.

There is rough travel, and then there is travel in sub-Saharan Africa. And there is no quicker way to reveal the true character of a collaborator than when things don’t quite go as planned. Reporting from remote locations means placing your fate in the hands of strangers—friends of friends, at best. It isn’t uncommon to ask yourself, “Was I out of my mind thinking I could pull this one off?”

Christopher Achobang was waiting outside the arrivals hall at Douala International Airport in Cameroon. Seeking cheap passage, I had taken a flight that arrived in the early hours of the morning. It’s a bad idea in most destinations, but it is plain foolish anywhere in Africa. Achobang, an environmental activist, suggested we leave crime-ridden Douala immediately and make haste to the quiet coastal town of Limbe in Anglophone, Cameroon.

At the edge of the city, the driver failed to notice the soldiers blowing their whistles at our car to stop at a checkpoint. After a minute or two, a Toyota pickup truck full of soldiers brandishing automatic weapons overtook us and cut us off with 45° maneuver, forcing us to an abrupt stop. I hadn’t been in Africa for 30 minutes.

My passport disappeared into an extended hand whose face was obscured by the blinding glare of a flashlight. I was now at the mercy of underpaid soldiers, after midnight on a lonely Cameroonian highway. No witnesses, not an electric light in sight. I sat, barely moving a muscle in the back seat, trying to measure any level of agitation in a language I could not understand. I found out I was in good hands with Achobang, who quickly calmed the man in charge with fearless cajoling, punctuated with laughter. Price settled, passport returned, we were allowed to continue, though the bribe would be part of my bill. Finally, I set up my mosquito net in a ramshackle bar-cum-hotel with only a slight idea of where I was, but the door had a lock and we had clean water to drink.

Oil rigs off the coast of Limbe in Southwest Cameroon. Cameroon is the seventh-largest oil producer in Africa, and is “richly endowed with mining assets,” according to the U.S. Embassy in Yaounde, though the mining sector contributes less than 1% to the economy. More tellingly, Cameroon currently ranks 63rd of 74 developing countries in technical skill development, according to the United Nations Industrial Development Organization. The World Bank estimated Cameroon’s 2009 unemployment at 30% (mostly youths), and its overall poverty rate at close to 40%.

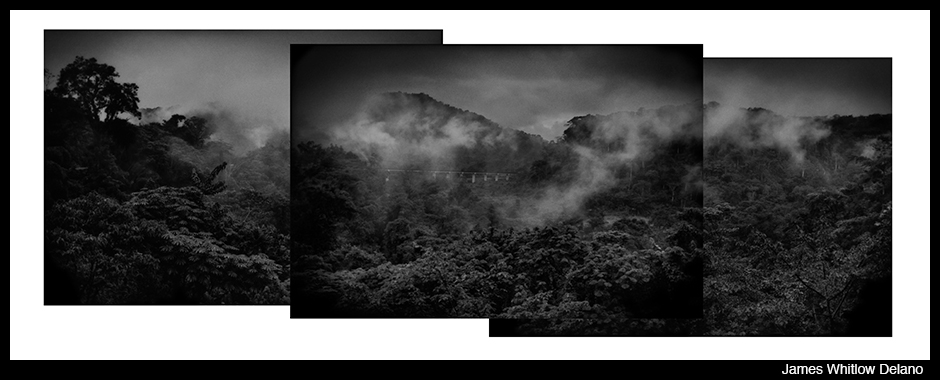

I had come to Cameroon after Bloomberg.com accepted my proposal to document the remote villages situated between five protected parks and sanctuaries. There, an American investment firm, Herakles Capital, planned to clear 73,086 hectares (180,599 acres) of forest. It was to be carved from the largest contiguous expanse left in the Guinean Rainforest, which once blanketed the entire Atlantic coast of West Africa. In its place—a stretch of land 10 times the size of Manhattan sheltering populations of lowland gorillas, chimpanzees, forest elephants, threatened drill primates, and more than 14,000 people living in relative harmony within this great forest —the company wanted to install a massive oil-palm plantation, Herakles Farms.

Nestled against the Nigerian border, the Anglophone areas formerly known as British Cameroons is one of the wettest places on earth, and this was the rainiest time of year. The more populous French side of Cameroon holds most of the power, and apart from a few cities, little of the Anglophone Cameroon even has electricity. I had been warned about the roads, but how much worse could they been than roads I had seen in Borneo or Suriname? I was chasing a story, and one way or another, I was going to get there.

The paved road ended in Kumba, where we loaded our bags on top of a four-wheel drive Toyota pickup. In preparation, I had wrapped my large pack in three layers of plastic sacks like the ones the dry cleaner uses to protect a wool coat or pressed suit. My computer, cameras and film were packed into my small backpack, which would stay with me inside the cab. In the tropics, I always slip a heavy-duty trash bag inside the smaller backpack to keep rain off my gear. I never use a camera bag, and the interior of the pack is only accessible from the top, which is closed tight by a drawstring and a buckle to stymie the most dexterous pickpockets.

People notice Christopher Achobang. He is a mountain of a man, but his penetrating eyes, infectious smile and sharp intelligence draw people to him; the man oozes benevolent confidence. In Africa, where money makes the “Big Man,” he is of humble means. And though strong as an elephant, he is not violent.

Activist Christopher Achobang rides on the back of a motorbike on the way to visit villages that abut the proposed Herakles Farm logging/oil-palm concession and Korup National Park. The concession sits south of the road, but villagers have been kept uninformed, so that even village chiefs are not sure where the Herakles Farm concession boundaries are. There is great concern about the future among local farmers and hunters.

A ferocious argument breaks out in front of us, since hours have passed and the Toyota hasn’t gone anywhere. Our destination, Nguti, is a four-hour drive, even though it is just 96 km (60 miles) away. Still, the sun sets at 6:00 p.m. sharp along the equator, and although though we’d arrived in Kumba at noon, by 3:00 p.m., the truck still had not budged.

At about 4:00 p.m., the driver finally fired up the engine, meaning we’d arrive in Nguti, well after sundown. The muddy road entered wild country, where giant rainforest trees crowd the road. Cacao is the local cash crop, and farmers protect the biggest trees since cacao grows best in the undercanopy, shaded by their crowns.

Near Ayong, Cameroon. Cacao, the main ingredient of chocolate, is the main cash crop for small farmers in the Herakles Farms project area. Many towering rainforest trees are left standing over the farms to shade the cacao trees, as they thrive in filtered sunlight, decreasing the impact on the local forest. Farmers also grow cassava, bananas, squash and maize (corn) for subsistence. Oil palm is grown locally and processed on an artisanal basis to supply the local market.

Soon, dusk settled in, and the road had deteriorated into a gauntlet of muddy quagmires. Farmers were walking home along the outer fringe of the road. Four-wheel drives fish-tailed, trying to maintain control.

East of Nguti, Cameroon. A young boy struggles to return to his village with the harvest from his family’s farm plot, his father trailing behind along a muddy road rutted by logging trucks. Logging trucks ruin roads locals have used for generations, making it difficult to walk along them, let alone navigate them with a vehicle. The road damage is due to selective logging deep in the rainforest; Herakles Farms would clear-cut forest close to the road to convert it to an oil-palm plantation, completely decimating the environment and dislocating farmers.

Suddenly, everything came to a halt. A two-wheel drive van was buried up to the floorboards ahead, going nowhere and holding up traffic. Motorcycles shimmied through the ruts and then, slowly, four-wheel drive trucks pushed past with passengers heaving from behind. The road was easily the worst I’d ever seen. Better drivers seemed to defy physics, willing their vehicles through the troughs.

Cameroon. The beginning of the drive from Kumba to Nguti, which would culminate in a midnight rollover into a mud puddle on a remote stretch of this road. Anglophone Southwest Cameroon has poor infrastructure compared with the politically dominant Francophone part of the country. The Herakles Farm project promised to improve infrastructure, but as yet, there is no discernible change.

Night set in. I sat in the middle of the front seat trying to avoid the stick shift, with the driver on my left and Achobang riding shotgun. A couple of hours into the trip, the driver revealed that this was his very first journey up this route. Ours was the slowest vehicle on the road. We were nearly eight hours into a four-hour journey because the truck had to be captured and freed from the muck several times, only to get stuck again.

Near Kumbe Bakundo, Cameroon. Not far from the fringes of the planned Herakles Farms oil-palm plantation, the Cameroonian rainforest crowds an orphaned concrete viaduct, which is met on both sides by muddy quagmires that make travel treacherous, especially during the rainy season. There is a noticeable lack of infrastructure in Cameroon’s Anglophone rural Southwest; highways are unpaved and there is little electrical service, compared with the more politically powerful Francophone regions.

Midnight was approaching when the truck mounted a pristine concrete viaduct built in the heart of the jungle, compliments of the South Korean government. The speed picked up, but so did the rain. The road before the viaduct was all mud and, at the end of a short respite, we were back in the slop again. The heavens opened, and holes in the road held massive puddles of unknown depth. The Toyota mounted a narrow log bridge over a rain-swollen river, sliding alarmingly toward the water. By this point, Achobang was loudly denouncing the driver for his lack of expertise.

Logging trucks penetrating the pristine interior forest have reduced the road to a rain-choked pond perfect for breeding malaria mosquitoes. Herakles Farms’ would be close to this location, though Herakles would clear-cut the forest to convert it to an oil-palm plantation, decimating the environment and dislocating farmers.

The truck came up over a lip and into a deep hole as wide as the road, and filled with water. The headlights illuminated a steep bank on the far side of the trough. I remember thinking that only the left wheel was climbing, as the top-heavy truck slowly lurched right toward the point of no return. The driver didn’t ease up on the throttle even as the truck tipped, until it capsized onto its right side in a meter-deep puddle. Somehow, the driver fell past me and I ended up on top of everyone as water began flooding the cab. My body felt heavy, the strap of my pack looped on my shoulder as I attempted to pull myself up using the steering wheel.

I shouted out, “Christopher, can you breathe?!” I knew that my weight was holding him down and there was nothing I could do about it but to claw my way up. He responded that he could. I threaded my right leg through the steering wheel, lifting myself out into the torrents of rain. Setting my pack down in a high spot, I ran back to help Christopher out of the cab. Attention quickly turned to passenger safety and assessing the damage to baggage. By good fortune, my big pack had been on the side of the truck that remained above the water line.

Achobang grabbed my large pack and put it on his head, and I carried his backpack and mine as we set off into the dark night. We passed through a village without knowing it, since there was no electricity. In the next village, there was light and loud music pouring from a shack. “We can get dry in that bar,” Christopher said, but it was not a bar. A couple of drunk, tiny men were joylessly dancing on the porch like Shakespearean jesters. An old woman, just as intoxicated, was slumped in a chair. The jesters beckoned us in. “What the hell is going on here?” I asked.

We had blundered into a funeral. Two members of this family had died in the past week, and their bodies were buried under the earthen porch. The jesters were literally dancing on fresh graves. One of the them tearfully declared that Achobang was his long-lost father. I settled in. Sunrise could not come fast enough.

Dawn arrived cold and wet, but welcome. I roused a snoring Achobang and we set off to find a car for Nguti. There were cars parked in a small village market. There was also what looked like a child sleeping on a table, wrapped in a damp blanket. It turned out to be a young woman, too weak and shriveled to return our salutation. She looked very ill—perhaps on the verge of death. After locating a driver, we turned to leave and I signaled to Achobang that we should give this woman a lift. She was trying to get to a district hospital up the road in Manyemen. By mid-morning, Christopher and I finally rolled into Nguti, having delivered the woman to the hospital. Finally, work could begin.

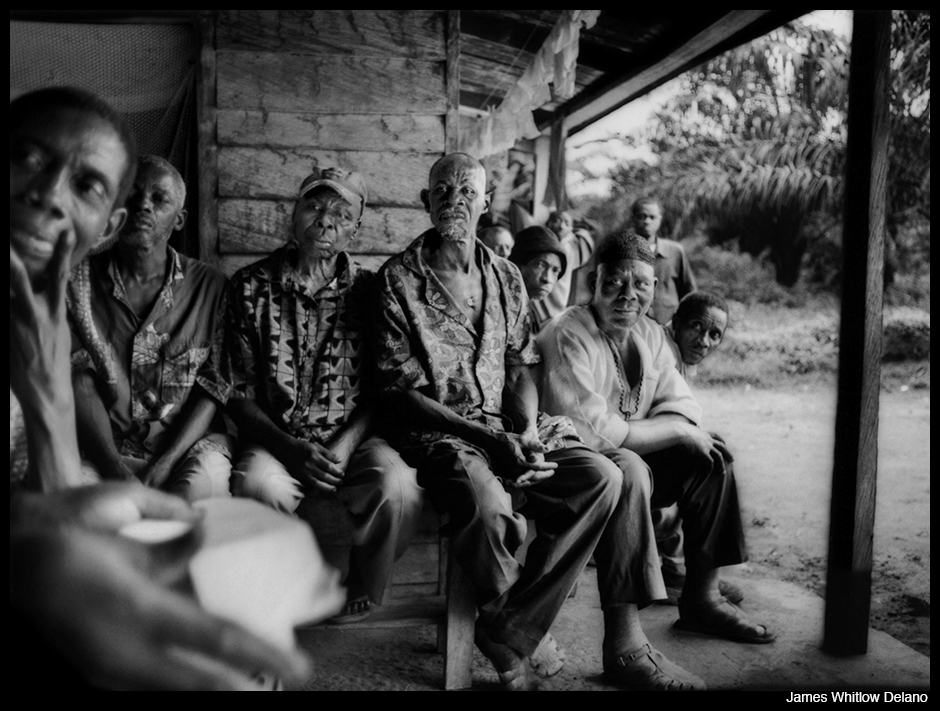

Sikam, Cameroon. Activist Christopher Achobang addresses villagers in the village of Sikam, which abuts the proposed Herakles Farms logging/oil-palm concession and Korup National Park. The concession runs along the southern part of their ancestral land and there is great concern about what the future holds if access to the forest is denied, or the forest is cut down and converted to a monoculture oil-palm plantation. Loggers on the northern fringe of their land have already cut down large trees and left them to rot.

Several days later, Christopher Achobang has the villagers of Sikam spellbound. Their village sits on the northern boundary of the proposed Herakles Farms oil-palm project. Villagers may soon risk arrest for trespassing simply by entering much of their soon-to-be-former farmland and former ancestral hunting grounds south of the road that bisects the village. “Slavery is over. The chains are cut. Are you going to put them back on?” Achobang asks. “They want to keep you off your land, cut down your forest.”

There are murmurs of agreement as Achobang’s monologue begins to take on a call-and-response rhythm. He has little difficulty finding common ground with the villagers, who believe that the spirits of their dead ancestors inhabit the giant trees. To cut down these trees, they believe, would be to kill the vessels that harbor the souls of their ancestors.

Sikam, Cameroon. Villagers listen intently to ways to prevent the Herakles Farms project from coming to fruition. The concession runs along the southern part of their ancestral lands.

Achobang has his enemies, though. Cameroon is the kind of country where activists who draw too much attention often disappear. It’s not hard to lose a body in the thick forest. But he also has a multitude of friends. He could have easily cut-and-run in the heat of the moment when he picked me up a couple of nights before, but he kept his word. Lifelong bonds are built on shared hardship.

Talangaye. Cameroon. Illegally felled trees at Herakles Farms’ nursery.

Talangaye, Cameroon. A peek at what is supposed to be out of sight: Herakles Farms’ massive, illegal oil-palm plantation.

At the time of this report, Greenpeace says that Herakles Farms has failed to obtain a presidential decree permitting its land clearance operations. Only by hiking covertly through an adjacent forest led by a Herakles Farms employee was it possible to see this nursery—which was to be the first step in creating a vast oil-palm plantation on a swath of land 10 times the size of Manhattan that links two national parks, two forest reserves and a wildlife sanctuary. Now, according to Greenpeace, the size of the proposed concession has been reduced to roughly 20,000 hectares (49,421 acres)—still more than twice the size of Manhattan. And that’s for three years … of a lease that could be extended for 99.

TRANSCRIPT and PHOTOGRAPHS by James Whitlow Delano. Edited by Ian Murphy. See previous dispatches here.

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus