Notes

Ode to Light: Making Street Photography in a Cynical Age — by Amy Touchette

Bedford Avenue, Williamsburg Brooklyn, 2014.

Bedford Avenue, Williamsburg Brooklyn, 2014.

The people of New York are what drew me to photography. The medium itself only played a supportive role. When I moved to New York City in 1997, my favorite thing to do was ride the subway. Each subway car seemed to hold a distillation of the world’s diversity, and that was an unusual setting for me. I was raised in a suburb of Syracuse, New York, in a homogenous school district, and although I had lived in Washington, D.C. and San Francisco before I moved to New York, I wasn’t used to being so engaged by humanity.

People watching became a daily hobby as I went about my life as a New Yorker. I didn’t question why. I just knew it stirred an energy in me that was positive. Four years later, when September 11th happened, I had a desperate urge to feel that energy as much as possible, as often as possible. I was living on Bleecker Street in Manhattan in an area that was blocked off to cars for a week or so after the attack. Outside my door was a scene out of an apocalyptic Hollywood movie: streets, eerily empty of cars, riddled with posters of dead people and their family’s despondent pleas to find them, and an indescribable stench of death and destruction constantly wafting in the air, the memory of which still haunts me.

Sunshine Cinema, Manhattan, 2014.

Nothing unearths truths quite like a dose of mortality. Within a month I enrolled in a Photo I class at the International Center of Photography (ICP) with the street photographer Jeff Mermelstein. I didn’t know how to operate a manual camera and I had never been in a darkroom, but based on my gut, which had a very strong presence at the time, I had a feeling photography could help me make my life more of what it needed to be. I was right.

The first photographs I made were of strangers on the street using a 35mm camera. I remember feeling shy and uncomfortable, but so excited. I had no idea why I wanted to photograph certain people and not others. I just kept following the path of inspiration. I took many more continuing education courses at ICP and read and looked at countless photography books. The joy of life that Helen Levitt preserved, the intensity of the urban setting that Bruce Davidson captured, the rumination on humanity that Garry Winogrand provoked, the inclusiveness of August Sander’s portraits, and the honesty of the Maysles Brothers’ documentary films all validated my need to record life.

Ludlow Street, Lower East Side, Manhattan, 2014.

But, most importantly, Diane Arbus showed me how to use fear as a muse on the street. Her tender portraits seemed to break down the wall between her and her subjects. Her photographs are in fact portraits of fear conquered: her fear of approaching strangers so unlike herself and their fear of revealing themselves to someone like her. Her respectful encounters made me realize that what I found frightening about taking pictures of strangers is not that I am stealing something from them, but that I am telling them, with my camera, that I like them, that I find them compelling, and that I want to remember them just as they are at that very moment. We so rarely express positive feelings towards strangers, but that’s exactly what’s at the heart of all well-meaning portraiture.

After several years of photographing spontaneously on the streets of New York, I started to notice certain patterns. Witnessing so much diversity made me want to compile like people with like people to see how they compared and contrasted. I started making formal portraits of people I encountered who reflected these patterns using a medium format camera. I would introduce myself, give them some direction, take two frames, and within two minutes they’d be on their way again.

N 8 Street, Williamsburg, Brooklyn, 2013.

It was a totally different way of working. In some ways it was easier: instead of blending in and anticipating the right moment to make a candid portrait, I could just ask someone directly for their time and focus on getting what I was after. In other ways it was more difficult: being upfront about my motives and convincing someone within a few words to even listen to me required different approaches each time, depending on the person and what I’d caught them in the midst of. The challenge that followed was equally hard: getting them to relax in front of the camera basically right away.

About 70 percent of the people I approached allowed me to photograph them. But like any red-blooded photographer, I never stopped lamenting the people and moments I wasn’t given permission to memorialize. And though I had made a pact with myself when I began photographing that I would never take a picture of someone who didn’t want to be photographed, when I got my first digital camera—my smartphone—I started photographing everywhere, including in these shadow areas.

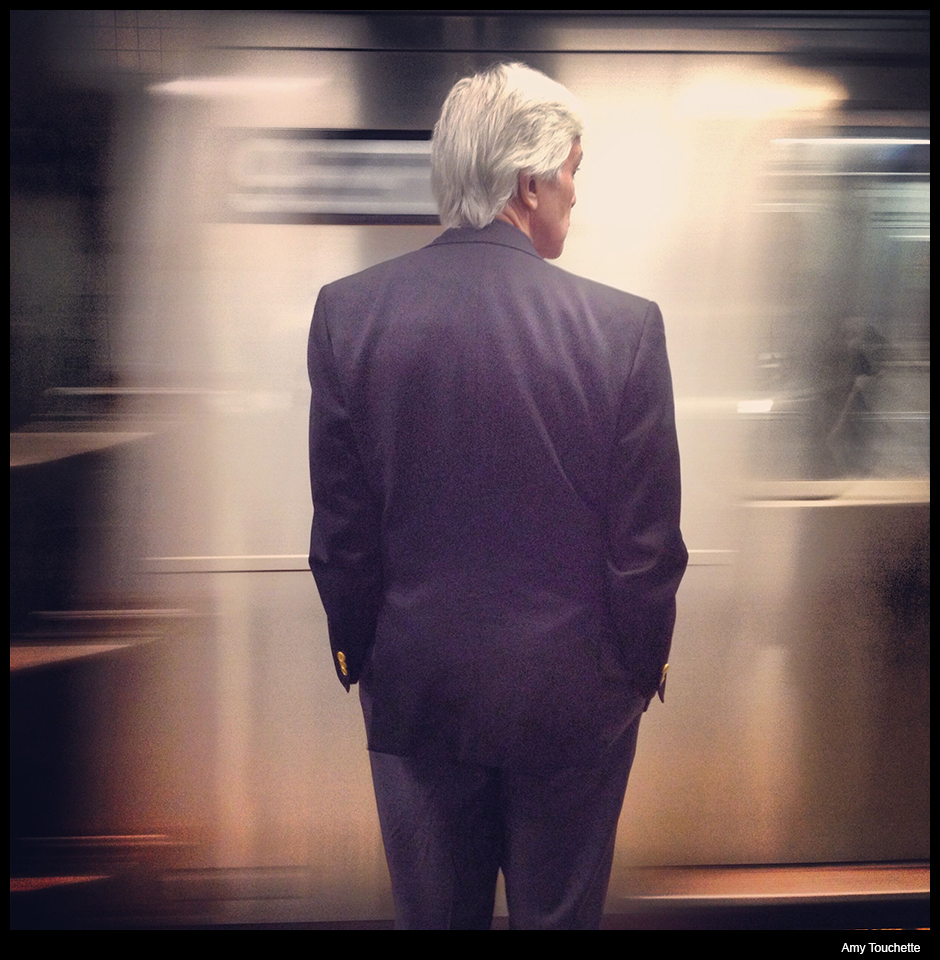

ACE Train, 14 St Station, 2013.

Every camera has distinct features to exploit, and one of the smartphone camera’s is that it’s always there. This alone set me free. All those in-between moments I couldn’t photograph because my film camera wasn’t on me were painful experiences of the past. Another is that the images smartphones make are subpar in resolution, size, and lowlight capture compared to other digital cameras. As a result, its pictures can’t be taken too seriously, and the psychological liberation that results from that is unprecedented. Being free to make errors, to visually jot down casual ideas, and to blow past boundaries that were previously tied to expense, resources, and effort has been a true gift. A smartphone is the sketchpad photographers have never had and the effects of that newfound playfulness and liberation are lovely and profound.

Broadway, Williamsburg Brooklyn, 2014.

Photographing with a phone can also be somewhat covert, and for certain street photographers that feature is particularly useful. Not because putting something over on someone is desirable, but because candid images of life are really difficult to make when people know they are being photographed. We tense up, we change our position, we think about our appearance, and by then an entirely different visual situation has manifested.

It’s not a new problem for street photographers, and using clandestine techniques to overcome it is not a new solution. Walker Evans made surreptitious photographs of people on the subway from 1938 to 1941 by painting the chrome on his camera black and hiding his camera so only the lens peeked out of his coat. He even went so far as asking Helen Levitt to accompany him, thinking he’d be less noticeable with a companion. The result is a collection of images of tremendous historic value that not only let us peer into and preserve that long-gone time, but also elicit remarkable comfort in proving that certain human experiences span the ages.

G Train, Greenpoint, Brooklyn, 2014.

G Train, Greenpoint, Brooklyn, 2014.

To me, the fruits of that work are invaluable, and creating some of my own from today is what keeps me sane, optimistic, and engaged in a world that can easily be seen as vapid, tragic, unjust, and disconnected. Without photography, how would we know who we are and where we came from? Even a mother can’t remember precisely how her child looked at six months old without a picture there to remind her. And that’s just one example of photography’s unfathomable time-bending feats. Pictures enhance the moments in our lives in a way that’s impossible to quantify.

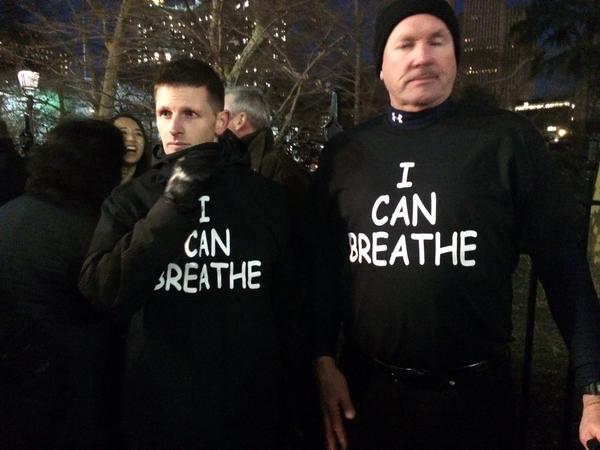

But today, photography’s reputation has grown complicated. People often regard it with suspicion. It’s been marred by the proliferation of surveillance cameras, the ability to share images with the world instantaneously, the support for shameless paparazzi coverage, and our unconscionable rising penchant for making fun of and taking down others (especially when we can do so anonymously). Photography is associated with maliciousness, distrust, and exploitation more than ever, instead of what it feels to be to me: a shy overture of admiration.

Manhattan Avenue, Greenpoint, Brooklyn, 2013.

Of course every era presents its challenges. It’s a waste to dwell on the ways things have gotten worse, which is why I hesitate even putting it into words. But I know that if I’m to continue making photographs of the general public, I need to be aware of the context in which we live. I’m ready to explain to people that they are beautiful, that they are unique, and that they are worthy of being recognized, even if they, themselves, don’t believe it (most don’t). I can’t stop wanting to capture the innocent exuberance of teenagers sitting on a stoop without them striking a pose, even though that requires not asking permission beforehand. And I can’t stop wanting to preserve all the colorfully stern, sage-looking older Polish women in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, who refuse to let me photograph them with my traditional camera, but whose picture I can sneak with my phone on Manhattan Avenue. Am I immoral for going against someone’s wishes because they don’t realize the light they provide? Can the end justify the means in this case?

Cafe Riviera, Greenpoint, Brooklyn, 2014.

No process is perfect and street photography is certainly no exception. But I know deep down that looking at each other is not only fundamentally positive, but crucial. Making street photographs helps me celebrate being alive. And more than anything I want to continue to share what I find right with this world.

Amy Touchette’s show of smartphone images, Street Dailies, runs until Jan 9, 2015, at Max Fish, 120 Orchard Street, NYC.

Photographs and text by Amy Touchette.

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus