Notes

Sarah Stacke: Proof of Existence in Manenberg

Love From Manenberg is not about gangs, poverty, or drug abuse, even though all of those things exist there. It is about how messy life is, and about the relationships photographer Sarah Stacke made and maintains in this Cape Town suburb. This is the fourth installment in an ongoing series.

Charmaine standing over Ashwin’s body at the viewing in their living room. Two of Charmaine’s daughters stand at her side. Photo by Sam Reinders.

After Ashwin was killed in a gang-related shooting on December 21 in Manenberg his body was taken to the State morgue in Salt River. The date of his funeral was set and then delayed, and then delayed again, and again. It turned out the only person who could roll his fingerprints –– or so his family was told –– was on holiday through the first week of January. I arrived in Cape Town on January 3 determined to attend Ashwin’s funeral. I didn’t make it; his funeral was the morning of January 13, over three weeks after his death and two days after I returned to the States.

Charmaine, Ashwin’s mother, didn’t register his birth when he was born 20 years ago. In South Africa this means that Ashwin essentially did not exist in any legal sense. Typically an identification of the body by a family member would suffice to release Ashwin from the morgue, but without a birth certificate or National ID, the only option was to have his fingerprints rolled and compared to his criminal record. Everyone told us how lucky we were that he had a criminal record; without it, the process could take months.

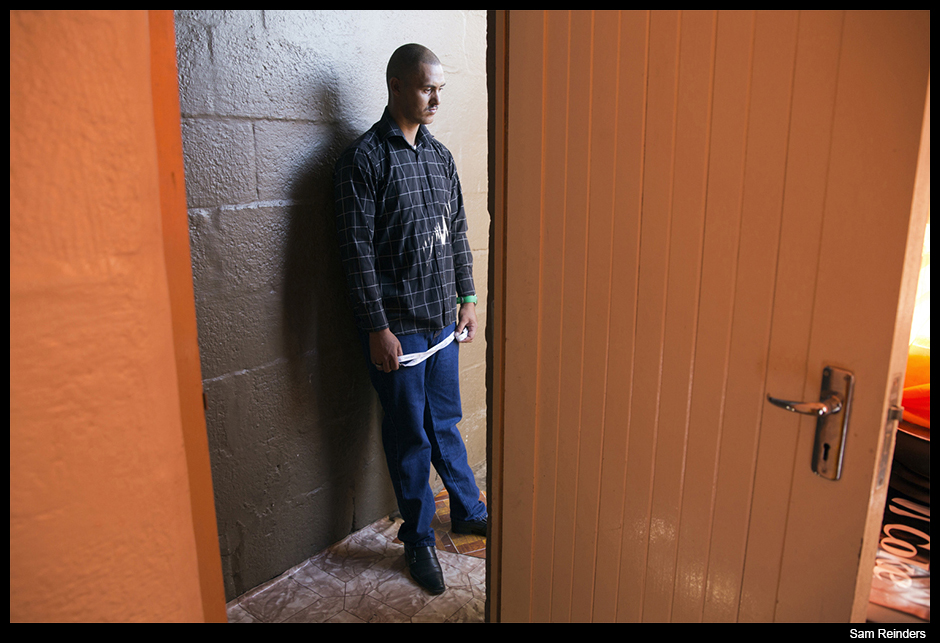

Randall, Ashwin’s brother, at the viewing. Randall’s home is connected to Charmaine’s.

Charmaine came with me the first time I visited the police station, the morgue, birth records at Groote Schuur Hospital, and the national archives trying to procure documentation of Ashwin’s identity and confirm a date for his release. Answers were elusive and Charmaine retreated to her home for comfort and her church for patience. I didn’t want to accept that Ashwin might stay in the morgue for months and continued asking questions and making visits to anyone and anyplace I thought could help. In the end, I don’t know if I expedited the process or just kept myself busy.

After Ashwin was released from the morgue he was taken to the mortuary where his body would be prepared for the viewing.

On January 9 Ashwin’s name reached the top of the forensic specialist’s list and he was released. His brother, Randall, and I identified the body. Charmaine chose not to join us. It would have been the first time she had seen Ashwin since he was shot outside their home. She couldn’t have reached through the glass to touch him, or comfort him, before leaving him in the hands of the State once again.

The viewing window was at the dead end of a long walk down a narrow breezeway. The attendant let us know he was going to start pulling back the blue curtain to reveal Ashwin. Only Ashwin’s face was visible. The plastic hid the coiled autopsy stitches, wrapped around his head, neck, and chest like a flesh-colored snake. Randall nodded and uttered, “Yes, that’s my brother.” I could only recognize Ashwin’s teeth, but maybe that’s the difference between knowing someone your whole life and knowing someone for two years.

A message taped on the kitchen wall inside Charmaine’s home.

I thought, although not consciously, that being part of Ashwin’s funeral and the events leading up to it would bring Ashwin’s family and me closer together. In many ways it did, yet it also pressured cultural gaps to the surface, like bubbles in a shaken drink. Gaps like this never dissolve completely, no matter how much time passes. They seem to move around changing size and shape, sometimes floating between us until they retreat.

Ashwin’s neice, Chante, running through the shipping containers where residents were relocated while the row houses were renovated. The gang fight in which Ashwin was killed lasted three months. During this time, construction on the row houses ceased, as it was too dangerous for the workers.

Charmaine was adamant that Ashwin be buried with the flag of the Hard Livings gang, of which Ashwin was a member, draped over his coffin. I still haven’t been able to fully wrap my brain around this, but I imagine it has something to do with not wanting her son’s death to be in vain–– he sacrificed his life for his gang brothers –– and respecting a force in her community that she is more familiar with than justice. And the family’s decision not to fight for an earlier release from the morgue, either because they didn’t want to, didn’t believe they were allowed, or didn’t know how, also rolls around in my mind. Where it lands is that this is the foundation of social exclusion, exactly what the architects of marginalization had in mind –– no voice.

Yes, there were other factors at play too. After Ashwin was killed family and friends contributed what they could to the cost of the funeral. After three weeks of daily needs, the money didn’t add up and Charmaine needed to find more resources. And there were other reasons too, that I will never know. Maybe I’m wrong and instead it boils down to my own misunderstanding of the system, but I can’t see a privileged family waiting three weeks to bury their son; having to close the coffin at the viewing because after weeks at the morgue, the smell was too much to bear.

Ashwin’s Hard Living brothers convening over his grave on the day of the burial. Photo by Sam Reinders.

My decision not to stay for the funeral involved the intersection between work and my family, and is something I still grapple with today. My friend and fellow photographer Sam Reinders selflessly offered to photograph it for Ashwin’s family, and for me. In the pictures I can see Charmaine standing next to Ashwin, her hand inside the coffin as she gently places a cotton ball close to his face in a gesture of comfort. Charmaine is serious, resigned maybe –– the corners of her mouth are drawn inward, likely an expression Ashwin knew well. When I see Ashwin at home at last surrounded by family and friends who are grieving, laughing, comforting –– all the emotions that one navigates with the pain of loss –– a sliver of peace is unexpectedly delivered. Talk about the power of photography.

Photographs and text by Sarah Stacke with additional photos by Sam Reinders

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus