Notes

Rita Leistner: Looking for Marshall McLuhan in Afghanistan

All new technologies bring on the cultural blues, just as the old ones evoke phantom pain after they have disappeared.

— Marshall McLuhan, War and Peace in the Global Village (p. 16)

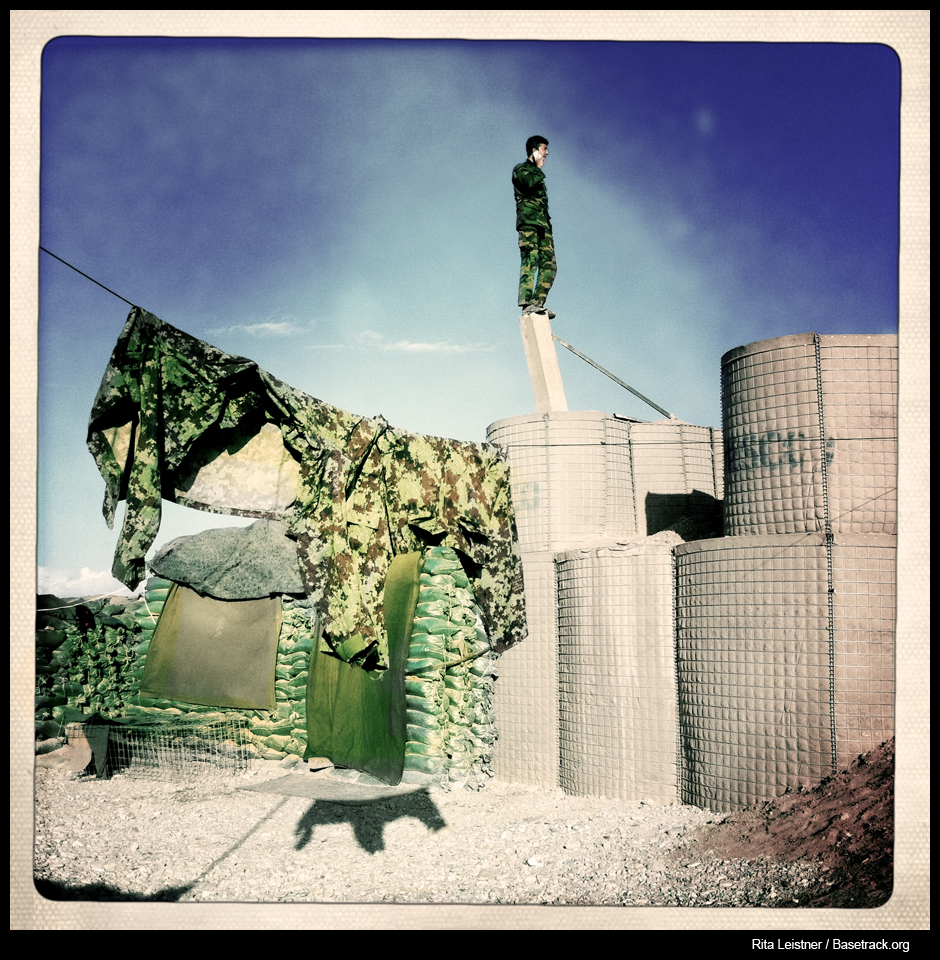

An ANA soldier attached to 1/8 searching for cell phone signal, 2011-01-29. Shir Ghazay Patrol Base, Landay Nawah County, Afghanistan. 1st Battalion 8th Marines Bravo Company 3rd Platoon.

I took this first photo of an Afghan National Army soldier making a call on his mobile phone, on January 29th, 2011 when I was working for Basetrack.org (1, 2) in Helmand Province. Readers may know Basetrack.org, Teru Kuwayama’s Knight Foundation-sponsored social media initiative embedded with the United States Marine Corps, 1st Battalion, 8th Marines (1-8). It was a great opportunity for me to go to Afghanistan, and to be part of a cool project that was pushing social media technologies to new extremes. In keeping with social media conventions, most of the team shot on iPhones using the Hipstamatic app. Before embarking on the trip, I’d never owned an iPhone; I’d never even taken a photograph on a mobile phone; I’d never used Twitter; and only reluctantly participated in Facebook (Facebook still pretty much gives me the creeps, even though I own some stocks in it). I’d be the first to admit I was and am not well suited to The Fast Art of Social Media. In fact, the very idea of sending a Tweet puts a sick feeling in my stomach and makes me want to retreat into a long novel, say War and Peace.

So this photo is one of the first I ever shot on a phone cam of any kind, and on the iPhone Hipstamatic app in particular. Already I could feel I was photographing a memory that wasn’t a memory I actually had. Most of my photography career has been spent working in non-fiction, and in the last two decades, principally in the hyper-realism of high-key color film (and now digital) and artificial lighting.

I could hardly believe the image when I saw it, and even less so now, even though the photo is a kind of evidence. It looks painted, and for an essay about mobile phones and phone cams, it seems staged. I didn’t know at the time that it would become an iconic image of my forays into Marshall McLuhan, technology, and war.

My friend Dr. Anthony Feinstein (author of several books on the psychological effects of covering war) once told me that a journalist’s therapy is in part tied up in the work itself—because we are confronting what we are seeing at the moment of recording it, and later in the acts of editing and publishing: So, our “talk-therapy” is built into the process. But what happens when our tools start putting greater and greater distances between what we see and what we get, or when so much of the process is over the moment we take the photograph? (the distance between action and reaction keeps getting smaller and smaller).

Marshall McLuhan argued that “the medium is the message;” that “with man his knowledge and the process of obtaining knowledge are of equal magnitude” (McLuhan, Understanding Media, Part I, Chapter 3, “Reversal of the Overheated Medium”).

Of course a photograph is only part of the process of photographic storytelling. In the case of this image, it began with an opportunity given me by Teru Kuwayama (an email message in December 2010: “What are you doing? Do you want to come to Afghanistan and work with us on Basetrack.org and shoot on an iPhone”?) (this is a paraphrase of a series of emails).

Hipstamatic was founded by Lucas Buick and Ryan Dorshorst and inspired by the Polaroid SX-70 single lens reflex Land camera (named after Polaroid founder Edwin Land). Buick and Dorshorst and the programmers they work with are like the “new chemists” in the equation of the once mechanical art, names in a lineage that includes Talbot, Daguerre and Nicéphore Niépce. The effect of the app is so much a part of the final image, that it makes sense to me to credit the developers in the images’ by-lines.

I think the Marines were suspicious of our high-tech but low-skill devices. Some said they thought at first it was a joke. And I believe the Afghans, who recognized we were people of some means, wondered why we weren’t using “real cameras.” I’m sure it crossed their minds that it was some sort of trick.

When a Master Gunnery Sergeant (the top military and weapons-tech guy in the Battalion) asked me what it was like to use an iPhone as a camera, I replied: “Imagine if one day all the expensive equipment you’d mastered, all your training, all your experience and knowledge, everything you’d spent your life sweating to learn, became obsolete, and was replaced with a Green Lantern Power Ring that anyone could use. That’s what using the iPhone as a camera feels like to me.”

McLuhan says technologies are “self-amputations of our own being” (War and Peace in the Global Village, p. 5). For sure we are deeply affected by them; just as those on whom we use our technologies are affected.

I took this next photograph shortly after I’d arrived in Helmand. My great friend and colleague Monica Campbell and I were following around one of the incoming commanders from the Battalion soon to be replacing 1-8. It was a mini press junket of two, and was meant to be a promotional photo op for the Battalion. What strikes me most about this photograph is what it says about different relationships to technology. Both the Marines and the Afghan National Army soldiers are equally self-conscious of the camera, but their self-consciousness is manifested in very different ways: The Afghans offer a full-frontal pose, a formal acknowledgement of the relationship between subject and apparatus. On the other hand, the Marines deliberately ignore the camera, so as to appear nonchalant, but they are no less posing. (I’ll be further exploring the effects of the technological gulf between the Americans and the Afghans in a later post).

1st Battalion 8th Marines (1-8) Musa Qala District Helmand Province, 2011-01-23. At Patrol Base (PB) Griffin near the town of Karamunda. 1-8 2nd Platoon Leader Lt. Jason Blydell shows around Maj Nathaniel Clayton, the Operations Officer of the 3-2. With them are the ANP (Afghan National Police) Commander Balazar (with beard) and another ANA soldier. When the 1-8 re-deploys home in March, they will be replaced by the 3-2, lead by Lt. Col Chris Dixon. Lt. Col Dixon spent three days in Musa Qala from January 21th to 24th being briefed and shown around area operations by 1-8 Commander Lt. Col Daniel Canfield.

As I mention earlier, I wasn’t so well suited to The Fast Art, and by the time the embed and the weeks spent in Kabul uploading images to the web and “feeding the beast” were over, I had a major feeling of un-resolve, verging on depression. The answer to my discontent, it turned out, was Marshall McLuhan. I came up with the title for an essay, “Looking for Marshall McLuhan in Afghanistan,” which was published as a twelve part series in The Literary Review of Canada and which, this summer, I’m expanding into a book.

Over the next few months, I’ll talk about what I’ve learned from Marshall McLuhan and how, by focusing on process, I’ve brought myself back to Slow Art Making and have found some peace of mind.

PHOTOGRAPHS by Rita Leistner / Basetrack.org

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus