Notes

Augmented Mannequins Figuring Prominently: The Globalization of Barbie

Based on the comically exaggerated mannequins popping up in Venezuelan storefronts, this amply illustrated NY Times article proves you no longer need Photoshop to bring together extreme proportions and the female form.

As the Times tells it, the mannequins are the brain child of factory owner Eliezer Alvarez, who “created the kind of woman he thought the public wanted—one with a bulging bosom and cantilevered buttocks.” The strategy worked, boosting sales enough so that Alvarez could build a new workshop. The article observes that “cosmetic procedures are so fashionable in Venezuela that a woman with implants is often casually referred to as ‘an operated woman,’” and points out that “mannequin makers jokingly refer to their creations as being ‘operated’ as well.”

Although the article suggests that the misproportioned mannequins match the aesthetic ideal of Venezuelan women, Meridith Kohut’s photo tells a different story. The female passersby captured in this image do not appear to be identifying with the new standard of Venezuelan beauty. They regard it, instead, with boredom, befuddlement, and disdain. The fact that the mannequin is displayed without arms suggests that the only parts of a woman that matter are those that can be sexualized.

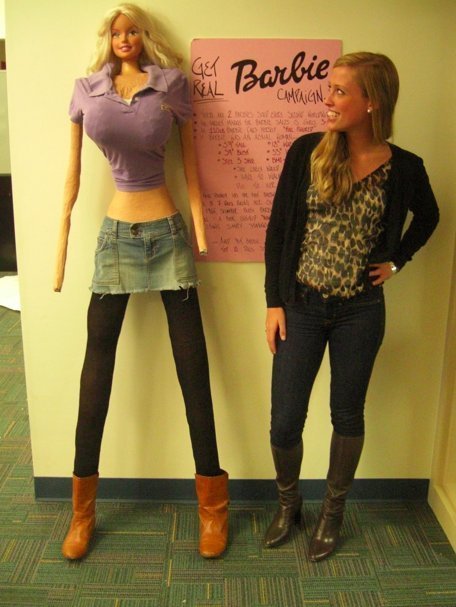

Scholar Jean Kilbourne has documented the ways in which the segmenting of women in fashion photography and advertising (removing or displaying fragmented body parts) dehumanizes women; Kilbourne explains that a mannequin has “no depth, no totality; she is an aggregate of parts that have been made acceptable.” It is, therefore, unsurprising that the real women in Kohut’s photo fail to approximate the mannequin’s body type, and her skin color is noticeably lighter than the photo’s other subjects. In fact, the mannequin’s narrow hips, broad bosom, and long legs resemble a U.S. American icon of unattainable beauty: Barbie. When student Galia Slayen constructed a life-size Barbie that kept the doll’s improbable proportions intact, the finished product resembled a more rudimentary version of Alvarez’s mannequins:

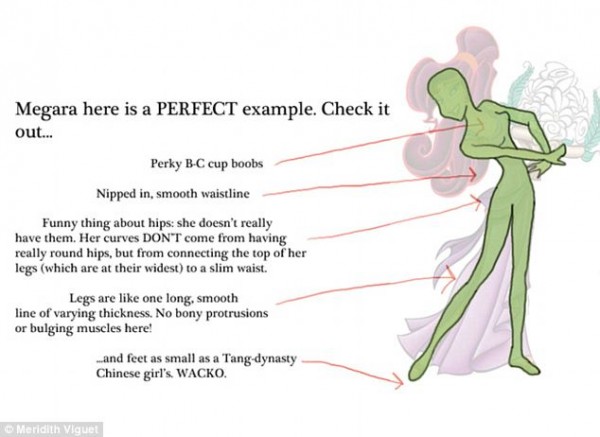

Slayen uses her Barbie to raise awareness about eating disorders, dressing her in a size 00 skirt that Slayen, herself, wore when she battled anorexia. This abnormal silhouette is common in U.S. popular culture. DeviantART user Oceanstarlet (a.k.a. Meridith Viguet) produced a satirical tutorial on how to draw a Disney Princess which highlights key features that echo Barbie and the Venezuelan mannequins: ample but perky breasts, narrow hips, long and lean legs, and “feet as small as a Tang-dynasty Chinese girl’s.”

For that reason, the New York Times’s ethnocentric exoticizing of the Venezuelan mannequins is misplaced. The market demand for products that convince women of the inadequacy of their natural bodies is a global phenomenon. Kohut’s photos hint at solution, however. After remembering that mannequins (like dolls and cartoons) are manufactured products produced largely by men for commercial purposes, we should begin to think about ways to turn dysfunctional icons of feminine beauty on their heads.

— Karrin Anderson | @KVAnderson

NY Times slideshow: An Exaggerated Vision of the Female Form in Venezuela

(photos 1, 3 & 4: Meridith Kohut for The New York Times: caption: “The transformation has been both of the woman and of the mannequin,” said Ms. Corro, the factory co-owner. photo 2: Galia Slayen via HuffPost. illustration: Oceanstarlet (a.k.a. Meridith Viguet)

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus