Notes

Between the Hajj and Hijab: New Picture of Islam for U.S. Audiences

Maybe it started with Malala Yousafzai’s now ubiquitous presence in Western media or with Ibtihaj Muhammad, fencing in hijab. Maybe it’s a reaction against the ugliness of Donald Trump’s image of Islam or maybe it’s an inevitable outcome of news cycles dominated by human-interest stories. Whatever the reason, mainstream news media in the United States appear to be having a moment about Islam, Muslim women, and the hijab.

Two photograph-rich stories published the very same day in major venues exemplify this moment. On September 14, Diaa Hadid of the New York Times offered a “Postcard from the Hajj” and Harmeet Kaur of CNN published “Hijabistas: Young Muslim women meld fashion and faith.” Certainly the end of the Hajj explains some of the timing for these articles, yet Kaur’s piece makes no mention of the famous pilgrimage. Are we seeing a new public picture of Islam emerge?

Hadid’s article is the second multimedia essay on the Hajj published in the Times this month. The first article, published September 7th, recounts one man’s story of the “crush accident” that occurred during last year’s Hajj, killing hundreds, maybe thousands of pilgrims. It offers a portrait of the Hajj as a constant press of people, a teeming space of religious ritual and risky proximity where people pack so closely together that their humanity is literally overrun and overruled by the mass. This is a familiar image of Islam, one fostered by “Clash of Civilizations” style depictions of the Muslim world and racist “skittles” analogies.

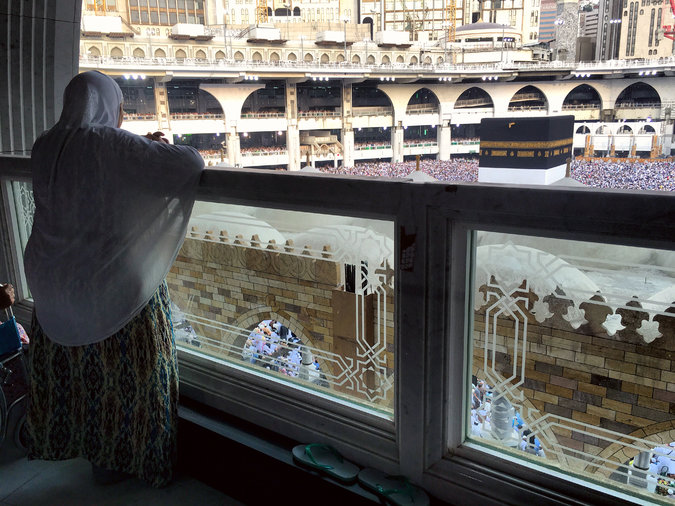

Hadid’s essay quite consciously offers another option—particular, personalized, and occasionally sardonic. It pairs a first-person view of the Hajj with a Q&A format in which Hadid offers friendly responses to questions posed by Times readers. The entire essay is punctuated by Hadid’s own photographs of the pilgrimage. Those photographs still show crowded scenes: tightly packed people throwing stones at the Jamarat Bridge and throngs surrounding the black box of the Kaaba. But even those mass pictures provide a protagonist whose presence brings the photographs into human scale.

Hadid’s photograph of the crowds at the Kaaba, for example, does feature a zoomed-out view where tiny people pack into the tight space of the Grand Mosque. However, we see that scene not from the air—as is common in Kaaba photographs—but from a balcony where we stand just behind a woman who has taken a moment to breathe during her walk around the House of God. She has been—and will again—be a part of the crowd, so the picture of the crowd becomes (however slightly) a picture of people in a crowd. Most of Hadid’s photographs take this approach, especially the photographs that feature women. The women stand or sit in pockets of space, individuals of poise and personality. Some gaze out of the photograph, fully aware of being viewed (though perhaps not aware of how large their audience might be); others clearly have no need of the audience, focusing instead on their pilgrimage.

Hadid’s “postcards” offer U.S. audiences an unusually close and familiar encounter with the crowded Hajj; Harmeet Kaur’s CNN slideshow showcasing Elin Berge’s photographs of high style among hijab women goes even further in reimagining the available picture of Islam. There are no crowds here, only scenes of air and light. And for the most part, even the sense of visual and physical confinement that defines Muslim womanhood in the Western-Christian imagination evaporates.

There is some coy play with Orientalism, as in the photograph of Iman Aldebe’s re-designed veil or the story’s opening photograph of a woman putting on makeup behind a sheer veil, but most of the photographs by Swedish photographer Elin Berge highlight their subjects’ self possession and confidence. These are twenty-first century women—business owners, savvy users of social media, entirely clear on the political implications of their choices. The caption of Berge’s photograph of Aldebe even winds up undermining its own Orientalist tendencies, quoting Aldebe’s observation that:

“When it comes to integration I believe fashion is a more effective way for change than any political labor market act. I started to modernize the veil when I realized how hard it is to get a job as a Muslim woman in a veil. You’re not seen as an individual with feelings and thoughts, so I wanted to highlight individuality. It worked. Girls got jobs dressed in my design. Fashion can open many doors.”

Despite my generally positive reaction to both the “Hijabista” photographs and Hadid’s postcard, I am still left pondering the implications of this visual shift from mass to individual and from male to female. Certainly these photographs—and the Instagram accounts that Kaur’s article links to—show an autonomy and independence that has historically been missing from Western-Christian representations of Muslim women. And certainly the first-person narrative has long served as a vehicle for shifting popular perception about larger communities.

Still, it is telling that women—as individuals—bear the burden of ‘softening’ or even ‘humanizing’ the typical picture of Islam in the United States. That these photographs have moved beyond the “poor oppressed Muslim woman” is notable and laudable. But still, the human dignity in these photographs is granted primarily through their individual scale and gendered lens. When we consider that the ubiquitous, problematic images of Muslims that circulate in the United States are predominantly pictures of men, of masses of refugees, or of seething, homogenous anti-American hatred, the quiet individuality of so many of these photographs is striking.

Berge’s photograph of Mariam Moufid at prayer in her Stockholm mosque (leading this post) nicely condenses this point: Moufid kneels on the floor. Seated rather than prostrate, she could as easily be in a yoga studio as a mosque. Most notably, rather than praying in community, she is absolutely alone in the spacious room. Her stylish, nude heels–just out of focus in the foreground–provide a subtle warrant for her status as a normal and absolutely unthreatening woman.

If this is, indeed, a new public picture of Islam for U.S. audiences, it is at once an improvement over the familiar, dehumanizing visual fare and a reminder that ‘they’re just like us, but in hijab’ is still a limited and limiting picture of 23% of the global population.

— Christa Olson | @christajolson

Photo: Elin Berge Caption: “Moufid prays in a Stockholm mosque” Photo 2: AP Photo. Caption: Muslim pilgrims and rescuers gather around people who were crushed by overcrowding in Mina, Saudi Arabia during the annual hajj pilgrimage on Thursday, Sept. 24, 2015. Hundreds were killed and injured, Saudi authorities said. Photo 3 : Diaa Hadid / The New York Times Caption: A woman paused during her circulations of the Kaaba at the Grand Mosque in Mecca. Photo 4: Elin Berge Caption: “Iman Aldebe poses for a photo. ‘Fashion can be political and start debates,’ she told Berge. ‘When it comes to integration I believe fashion is a more effective way for change than any political labor market act. I started to modernize the veil when I realized how hard it is to get a job as a Muslim woman in a veil. You’re not seen as an individual with feelings and thoughts, so I wanted to highlight individuality. It worked. Girls got jobs dressed in my design. Fashion can open many doors.’

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus