Notes

Cruel Looking: From Puerto Rico, and Beyond

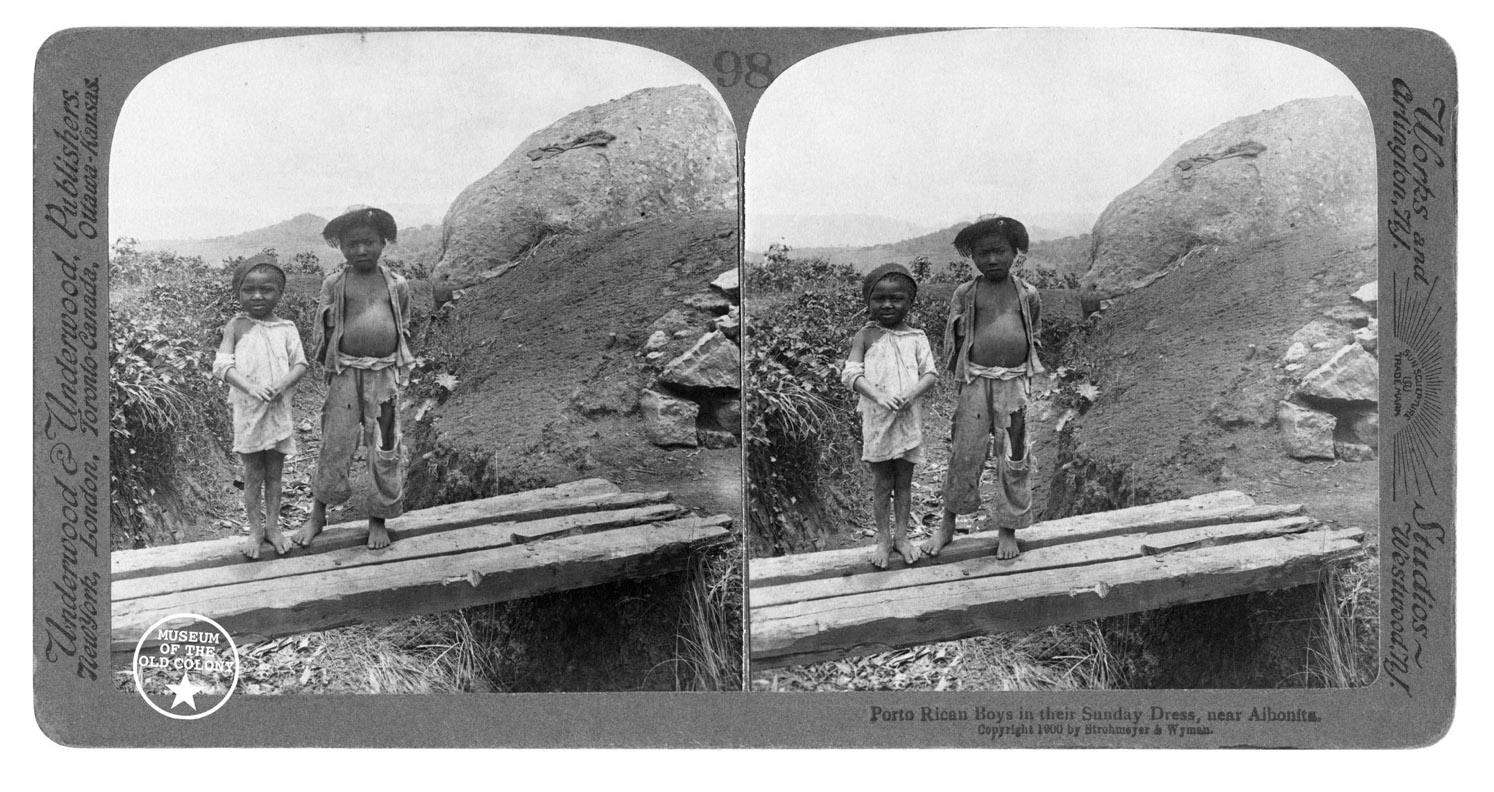

“Who with any heart, with any compassion, would make fun of boys wearing rags?”

This question, asked by Pablo Delano during an interview with the New York Times about his “Museum for the Old Colony” exhibit, has stuck with me over the last few weeks. It resonates with a question I often ask myself when looking at historical prints, photographs, and paintings that visually denigrate citizens of Central and South America: did the image-makers really not know that what they were doing was wrong? Like Delano, I simply do not accept the notion that different eras had different understandings of race, and so such practices of depiction and looking were morally neutral for audiences and image makers. They must have known, at some level, what they were doing.

Pablo Delano’s collection of historical photographs showing Puerto Rico draws from many sources. Some are stereographs, printed and sold for use by would-be tourists;. Others circulated publicly in the United States in the pages of National Geographic or in F. Tennyson Neely’s “Neely’s Panorama of Our New Possessions,” which celebrated the United States’ territorial acquisitions following the Spanish-American War. Still others come from official government reports and press offices. Most were produced by image makers from the United States, and they translate the Island for white audiences in the United States. In almost every case, callous superiority infuses captions and pictures. It is bad enough to photograph two children in torn clothes, bellies distended from hunger, and then sell those photographs to armchair tourists who want a taste of the distant and foreign. But then to make them into a cruel joke, describing them as dressed in their Sunday best? “Who with any heart, with any compassion…?” indeed.

They must have known that what they were doing was wrong.

And if you are about to suggest that I am ignoring differences in norms and expectations between then and now, let me remind you that the U.S. President made headlines just the other week when he re-tweeted anti-Muslim propaganda. Historical differences mean that President Trump’s actions were greeted with condemnation from the likes of Teresa May while Underwood & Underwood remained a prosperous purveyor of visual entertainment until the stereograph itself slid into oblivion. Neither, however, can be excused by their historical context.

Taking photographs always involves something of an ethical morass. That problem is exacerbated by differences of ethnicity, wealth, national identity, or natural disaster. Do you photograph a suffering child in order to raise awareness, risking exploitation, or do you leave the camera aside and risk the child’s circumstances falling into obscurity? These are old questions and complex ones.

I am pondering something much simpler today, though: the bald-faced choice to look cruelly. To gaze through the camera lens at someone different from ourselves and laugh, sneer, or degrade. Our world, our viewing practices today, are as prone to that cruelty as were the early years of Puerto Rico’s long (and on-going) colonial relationship with the United States.

President Trump’s criticism of San Juan Mayor, Carmen Yulín Cruz, and his repeated remarks about the limits on aid to be provided to Puerto Rico following Hurricane Maria likewise served as invitations for audiences in the mainland United States to look toward Puerto Rico with a mixture of superiority and exasperation.

Though mainstream media outlets repeatedly emphasized that Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens and no-one but the most puerile denizens of the Internet outwardly mocked displaced Puerto Ricans, the administration’s differential treatment of Texas, Florida, and Puerto Rico still invited mainland audiences to cruel looking.

On the one hand, President Trump was roundly criticized for tossing paper towels to Puerto Ricans seeking relief, and photographs showing the scene invited us to critique him. On the other hand, the sight of paper towels flying through the air still made light of the situation in Puerto Rico.

The wide circulation of that photograph—even as criticism—ran the risk of inviting dismissive views. After all, as one Washington Post article pointed out, “The mainstream media didn’t care about Puerto Rico until it became a Trump story.” And when the President repeatedly imagines Puerto Ricans as asking for too much, support is slow to arrive, and the aid offered is sub-par, images of that aid being distributed to U.S. citizens affected by a natural disaster can easily become scenes of problematic others who grasp what they didn’t earn and demand what they don’t deserve.

This pattern in which Puerto Rico and Puerto Ricans only matter when they tell mainland U.S. audiences about ourselves and our concerns has a long history, of course.

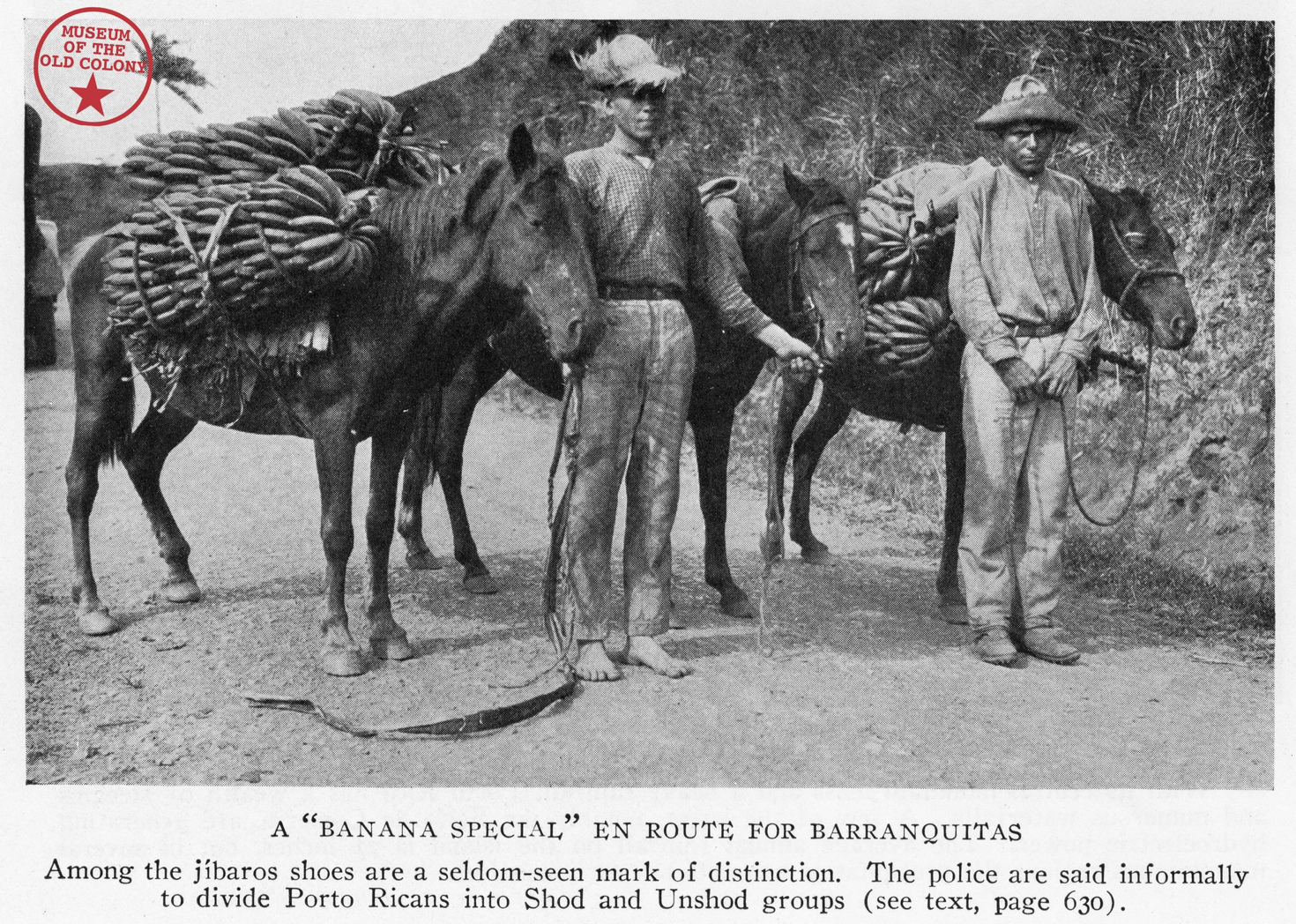

In 1924, National Geographic published “Porto Rico, the Gate of Riches.” Though the article’s sub-title simply translates the Spanish of Puerto Rico’s name, its photographs of Puerto Ricans reek with ironic distance from its titular richness. The snide reference to a “Banana Special” that implicitly contrasts Puerto Rican horses with U.S. trains. The faux scientific observation that “the police … divide Porto Ricans into Shod and Unshod groups.”

These and other aspects of the photograph above encourage ways of looking rooted in superiority, ethnocentrism, and—ultimately— self-satisfaction. The photograph itself, showing its subjects standing in defensive positions and gazing at us with lowered heads, invites cruel looking. And even if the first half of the 20th century did have different norms of behavior than we have today, viewers, image-makers, and caption writers had to know there was something wrong with how they were looking at the people who another photograph in Pablo Delano’s collection derisively calls “newly made Americans.”

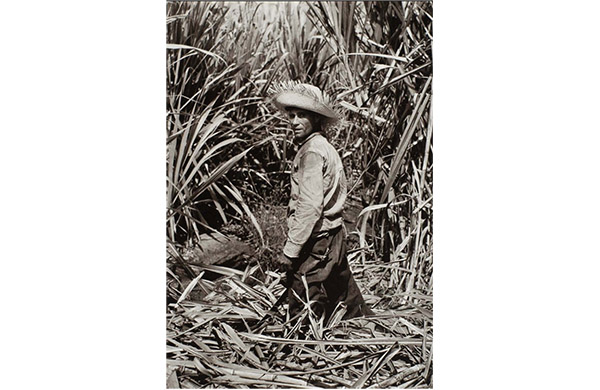

We can know that the photographers and viewers for National Geographic could have made other choices in part because just twenty years later, another photographer, Jack Delano—Pablo Delano’s father—made his name by producing beautiful, respectful pictures of Puerto Rico and Puerto Ricans.

We could, of course, critique Jack Delano’s photographs for romanticizing and objectifying their subjects in different ways. But Delano’s long relationship with Emiliano Pacheco Vega—the sugarcane worker shown above—echoes what is visible in the photograph as well: Delano’s pictures are categorically different from National Geographic’s. They evoke different ways of viewing. Vega’s wide stance, closed hand, and quizzical look speak of equality and engagement with the photographer and viewer. Dwarfed by the sugarcane, he is in no way diminished. There is no invitation to cruel sight here.

Yet the habit of looking cruelly is deeply ingrained and persistent. Our current political moment makes that abundantly clear. And it isn’t just visible in the United States’ colonial relationship with Puerto Rico. Whether President Trump is a cause or a symptom, cruel depictions of others are rampant today and so is our collective tendency to take pleasure in them. Candidate Trump’s mocking of a disabled reporter and President Trump’s recent re-tweet of anti-Muslim propaganda sit alongside bales of pictures mocking Trump’s own body. His repeated invitations for supporters to look cruelly at those he sees as racial, ethnic, religious, or gendered others are too numerous to cite.

There is something particularly ironic and insidious about the cruel looking that President Trump invited when, at a ceremony honoring Navajo “code talkers,” he took a swipe at Senator Elizabeth Warren. As many news outlets noted, the photographs and videos of that moment pin the Navajo elders who served as communications experts during World War II between President Trump and Andrew Jackson, between the racism of the present and the genocide of the past. Jackson’s eyes bore into the backs of the heroes supposedly being honored. President Trump’s back is to them as he descends into his own petty concerns. The available options are troublingly limiting: look cruelly or turn away.

All this has me thinking about the highly visual nature of human mistreatment. The November 27, 2017 issue of the New Yorker includes an essay by Paul Bloom arguing that when we degrade, mistreat, or do violence to others, the impulse for that cruelty comes not from our assumption that those others are less than human but from our recognition that they are human and our desire to strip that humanity from them.

In other words, the photographs in Pablo Delano’s collection whose primary purpose was to introduce Puerto Rico to U.S. viewers do not present those viewers with already dehumanized others. Instead, they invite visual participation in acts of shaming that were directed at other human beings in order to dehumanize them. Taking pleasure in seeing others’ shame was essential to establishing the viewer’s sense of superiority. Accomplishing that requires that audiences participate in intentional, active seeing. Showing the bodies of others—be they Puerto Rican children or British Muslims—and stripping them of dignity in full view: this is cruel looking. Knowing it is wrong is part of the plan. Pablo Delano encourages us to see in the “Museum of the Old Colony” echoes of the United States’ recent neglect of Puerto Ricans following Hurricane Maria. I suggest the echoes resonate much further.

— Christa Olson | @christajolson

***

This week, Reading the Pictures is asking for your support. We are the rare organization promoting visual literacy and media literacy at a time when both remain rare and essential. Help sustain our role as vigorous advocates for effective news and concerned photography with a tax-deductible donation here, or at the bottom of the post. Thanks so much.

***

(Photo 1: Museum of the Old Colony/Pablo Delano. Caption: “Porto Rican Boys in their Sunday Dress, near Aibonita.” Sourced from Stereo card by Strohmeyer and Wyman, New York, N.Y., sold by Underwood & Underwood, 1900. Photo 2: Evan Vucci/AP Caption: President Donald Trump tosses paper towels into a crowd as he hands out supplies at Calvary Chapel on October 3, 2017, in Guaynabo, Puerto Rico. Photo 3: Calos Giusti / Associated Press. Caption: Members of the National Guard distribute water and food after Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico. Photo 4: Museum of the Old Colony/Pablo Delano Caption: A ‘Banana Special’ en Route for Barranquitas.” Sourced from National Geographic, 1924, from the article, “Porto Rico, the Gate of Riches.” Photo 5: Jack Delano / General Archive of the Institute of Puerto Rican Culture. Caption: Emiliano Pacheco Vega (Don Toli) as a young caneworker, near Guayanilla. 1946. Photo 6: Oliver Contreras, Pool / Getty Images. Caption: U.S. President Donald Trump (R) speaks during an event honoring members of the Native American code talkers in the Oval Office of the White House, on November 27, 2017 in Washington, DC. Trump stated, “You were here long before any of us were here. Although we have a representative in Congress who they say was here a long time ago. They call her Pocahontas.” in reference to his nickname for Sen. Elizabeth Warren.)

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus