Notes

Photo of a Drowned Migrant Father and Daughter Is Fading Fast

Two weeks ago, we predicted in a post here that the photo of two drowning migrants, Óscar Alberto Martínez Ramírez and his daughter, represented a political tipping point. Below, visual scholar Jens Kjeldsen offers a different perspective, based on the workings of landmark news photographs.

It is a truly disturbing sight. A father and a toddler lying face down in the shallow waters of the Rio Bravo. The position of their bodies tells us instinctively that they are not alive. As in many captivating images, the details make it stand out. The t-shirt that holds them together creates a desire to reconstruct the dramatic story with the terrible ending. The little arm of 23 months old Valeria lies across the neck of her father, as if she is still trying to hold on to him. The diaper in the bright red shorts is filled with river water. We see them from above, as though we have just discovered them ourselves, while walking on the riverbank.

Julia Le Duc’s image was instantly published around the world: Not just in the US and Central America, but also in Latin America, the Middle East and Europe. Many papers published it on their front pages; even more published it inside the paper. The photograph quickly spread everywhere on social media and online outlets. This omnipresence demonstrates the immense power of agenda setting in unique photographs.

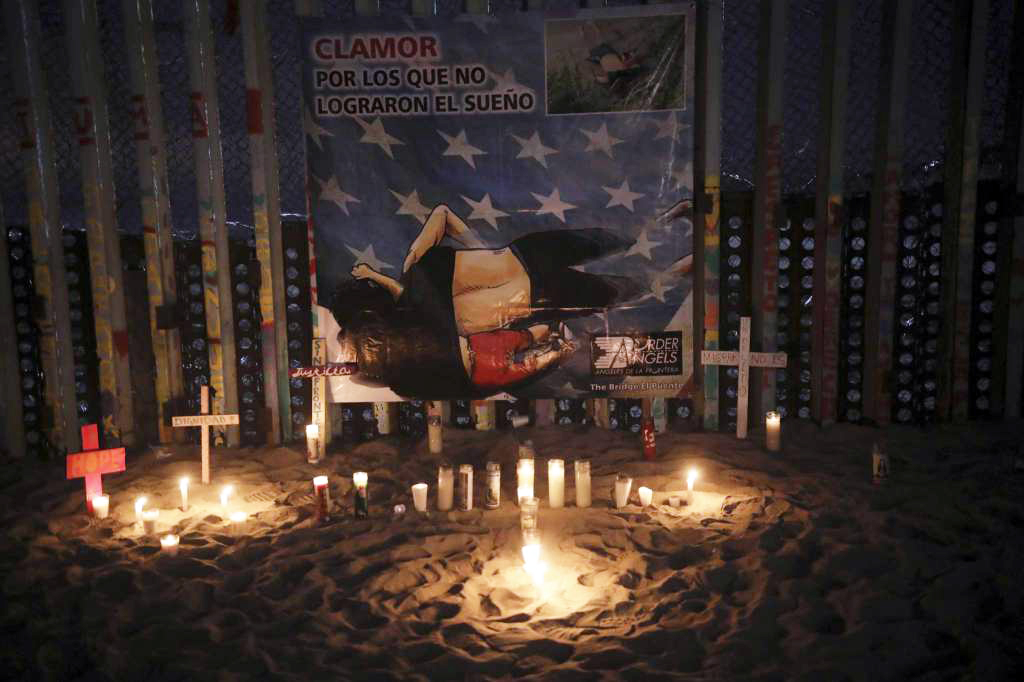

Simultaneously, the emotional impact the image released in newspapers and social media appears to signal, even create, a new situation. It stands out, and was perceived as a call to action. That impact is reflected in the illustration above at a make-shift memorial at the border fence in Tijuana.

However, the responses to the image followed recognizable paths of emotions and reasoning, which do not guarantee action. First, a strong, emotional upset that leads to moral outcry. The image is harrowing and heartbreaking, and the emotional response immediate: This is terrible and someone ought to do something about it! Then follows talk about the power of the picture and pointing to similar pictures from the past, to demonstrate this power – in this case, predictably, other pictures of children who suffered or died because of political circumstances. As soon as the media has found family and relatives, they then provide us with “the story behind the image.”

From a call to action, the image quickly transforms into a melodrama of a terrible death, changing the viewer-position from political activist to an emotionally charged, but passive spectator.

To put it bluntly: the belief in the picture’s power to change the agenda and create a new policy, often resides more in hope, than it does in what we actually know about photographs.

We have seen it before. The images from the Vietnam War are often brought out to bolster the claim that images change policies. Eddie Adams photograph of General Nguyen Ngoc Loan’s execution of a Vietcong prisoner (1968) and Nick Ut’s photograph of 9 year old Kim Phuc running from a napalm bombing (1973) are examples of images that allegedly changed the public opinion and eventually stopped the war.

However, can images of suffering really stop a war – or change immigration policy? In his book Photojournalism and Foreign Policy: Icons of Outrage in International Crisis (1998), David Perlmutter has demonstrated that even though strong images from Vietnam played a role, the withdrawal of American troops was first and foremost caused by reasons of Realpolitik.

Icons of outrage are open to interpretation, and they work on the basis of a first-person effect: I am touched by the power of this image, so others must be touched in the same way, and they will demand the same action. Thus, the power of icons of outrage is partly that people believe they have such power.

The most recent and similar instance of a picture that was commonly agreed to change everything, is Nilüfer Demir’s photograph from the refugee crisis of 2015, showing the body of three year old Alan Kurdi. The little boy drowned on a Turkish beach after his family tried to reach Greece with a small and overfilled boat.

Like the picture of Óscar Ramírez and his daughter Valeria, the photograph of Kurdi was believed to be able to change immigration policy and the situations for fleeing refugees. Now, four years later, we know that this is not the case. In the wake of the publication of the picture, many citizens of Europe did sign petitions to urge politicians to take in more refugees. European leaders, such as UK Prime Minister David Cameron, did promise to take in more. However, generally, the refugee policies of Europe are the same as before; some are even stricter.

In the aftermath of the deaths on Rio Bravo, we will probably experience the same in the U.S. Emotions of shock, outrage, and indignation are strong feelings, but they are short lived. They flare up, engage, and encourage action. Still, if action is not carried out immediately in connection with their eruption, they will fade and their activating power will evaporate.

We can expect photographic icons like the pictures of Alan Kurdi and of Óscar and Valeria Ramírez to move through three temporal phases of reception:

(1) Evoking: First they exercise a power of emotional presence and create attention and emotion and are seen as “a wakeup call.”

(2) Fading: Next, the meaning of the pictures are challenged, more general discussion ensues, the public moves on, and attention fades.

(3) Iconic renaissance: Finally, years after, because they are established and remembered as symbols for a specific event, people return to them when discussing this event.

They will then be used in new circumstances and debates, as we have seen with the photographs of Eddie Adams, Nick Ut, and Nilüfer Demir.

Fading can be a matter of days, weeks, or months, however we have already witnessed the beginning of the fading of Le Duc’s disturbing picture. While the outraged, convinced of the power of the picture, seem to consider the image an indisputable part of reality, the opponents treat it as a rhetorical sign that can be used and manipulated in the same way as words.

The minority leader and Senator of New York, Chuck Schumer, urged President Trump: “I want you to look at this photo. These are not drug dealers or vagrants or criminals; they are people simply fleeing a horrible situation.”

Trump found the photograph equally disturbing, but saw it as a reason to hold on to his own policy: “I hate it,” he said about the situation in the picture, “and it could stop immediately if the Democrats change the laws. […] If we had the right laws, that the Democrats are not letting us have, those people wouldn’t be coming up, they wouldn’t be trying,” Trump argued; “The asylum policy of the Democrats is responsible.”

President Trump blames the Democrats for the tragedy, the Democrats blame Trump. Already, in the immediate days after the deaths, the connection between the strong emotions demanding action and actual action became a verbal negotiation. “[T]he picture did little,” The New York Times wrote the same day, “to narrow the partisan divide over immigration policy.”

In the following days the fading of visual power continued. First, we learned that Óscar’s mother did not want them to go. They “migrated” only because of the economic situation,” she said to the New York Times. The photo shows Rosa Ramirez at her home in San Martin, El Salvador, looking at photos of her son and grandaughter five days after they passed.

In the following days the fading of visual power continued. First, we learned that Óscar’s mother did not want them to go. They “migrated” only because of the economic situation,” she said to the New York Times. The photo shows Rosa Ramirez at her home in San Martin, El Salvador, looking at photos of her son and grandaughter five days after they passed.

Then comes the reports of the wife of Óscar and mother of Valeria going back to El Salvador and the burial back home.

On July 1, Fox News and the Washington Post reported that the “Salvadoran president says his country is to blame for migrants drowning in Rio Grande.” The day after an opinion piece in the Washington Examiner argued that “Trump is right: Oscar and Valeria Ramirez might still be alive if the border were secure.” In short: While critics of the US government policies on immigration use the image as evidence for its failure, supporters of the policies use it as an argument for its necessity.

This rhetorical tug of war will suck the power of evoking and emotional presence out of the photograph. While it may be true that a picture tells a thousand words, a picture rarely speaks for itself. In the end, the visual power of the photograph of Óscar and Valeria Ramírez will depend on who wins the verbal war over the meaning of the picture.

–Jens E. Kjeldsen

(Photo: Emilio Espejel/AP. Caption: Candles are placed next to the border fence that separates Mexico from the United States, in memory of migrants who have died during their journey toward the U.S., in Tijuana, Mexico, late Saturday, June 29, 2019. On the border fence hangs a cartoon depiction of a news photograph of the bodies of Salvadoran migrant Óscar Alberto Martínez Ramírez and his daughter Valeria, who drowned on Sunday, June 23 on the banks of the Rio Grande between Matamoros, Mexico, and Brownsville, Texas; Photo 2: Antonio Valladares/AP Caption: Rosa Ramirez cries when shown a photograph printed from social media of her son Oscar Alberto Martinez Ramírez, 25, granddaughter Valeria, nearly 2, and her daughter-in-law Tania Vanessa Avalos, 21, while speaking to journalists at her home in San Martin, El Salvador, Tuesday, June 25, 2019. The drowned bodies of her son and granddaughter were located Monday morning on the banks of the Rio Grande, a day after the pair were swept away by the current when the young family tried to cross the river to Brownsville, Texas. Her daughter-in-law survived; Photo 3: Osman Orsal/Reuters Caption: A man holds a poster with a drawing depicting Aylan, a drowned Syrian toddler, during a demonstration for refugee rights in Istanbul, Turkey, September 3, 2015. The image of Aylan went viral on social media and piled pressure on European leaders. Photo 4: Screenshot Caption: On June 26, 2019, Senate Minority Leader Charles Schumer (D-N.Y.) displayed on the Senate floor Wednesday the photo that went viral this week of two drowned migrants in a direct appeal to President Trump over his immigration policies; Photo 5: Screenshot Caption: El Salvador’s President Nayib Bukele has said his country is to blame for the death of a father and daughter who drowned while trying to reach the U.S.)

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus