Notes

The Disappearing Island: Censorship at Guantánamo Bay

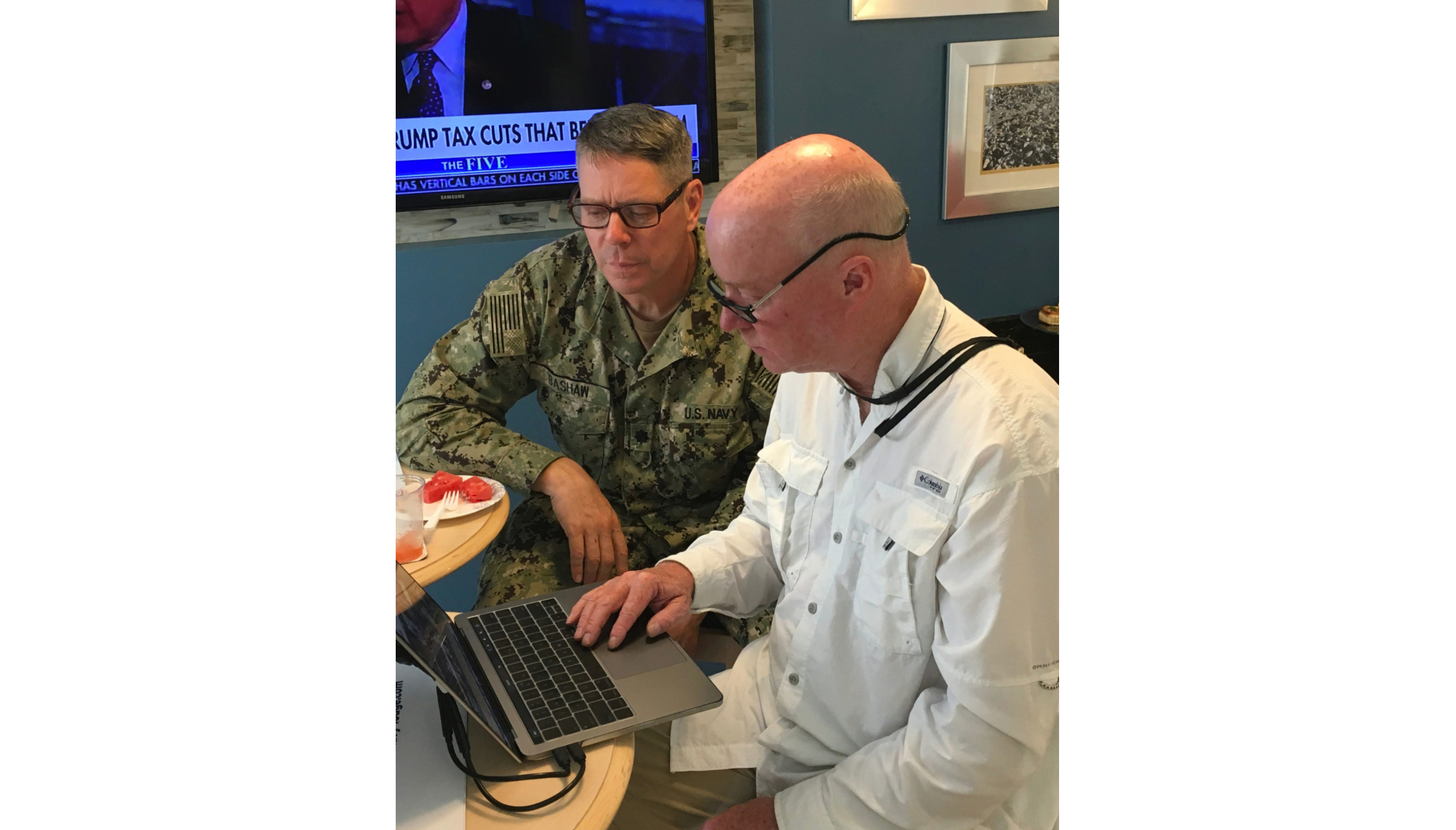

A recent New York Times photo-essay called “A Look Inside the Secretive World of Guantánamo Bay” ends not with pictures of men in orange jumpsuits or the cellblocks that house them — images that might have given us a glimpse “inside” the secretive world promised in the title. Instead, the essay ends with this picture of staff photographer Doug Mills and an official U.S. Navy reviewer in military fatigues, both looking at a laptop screen. Behind them, a TV broadcasts Fox News, while on the table a paper plate contains the remnants of a meal.

The caption to this photo casts a tense pall over this seemingly casual moment. It explains that during this security review, Mills, in the foreground, “had to delete as many as 40 percent of his images from the detention center.” As if putting this act of censorship on display, Mills leaves his hand on the mousepad as he submits his photos for the reviewer’s approval.

By definition, censorship results in denials to see, to hear, and to know. So how can censorship itself be depicted, especially with all the compromises media personnel have to make? And, an even more complicated question is how can journalists report on censorship without distracting from the story they set out to tell?

This conundrum has dogged journalists and photographers reporting on Guantánamo since 2002. That was when the Bush administration turned the military base into a detention facility to hold “enemy combatants,” a slippery, quasi-legal category created for men who were captured and detained as terrorists during the height of the War on Terror. Today, 40 of the acknowledged 779 prisoners remain, most of whom have been there for almost fourteen years. All but one still are being held without formal charges or trials.

For its part, the Department of Defense has done a complicated dance with media personnel, allowing them access to the prison but imposing tight restrictions. The military has offered guided tours for journalists since shortly after opening the facility. But it wasn’t until 2010 that the DoD, in consultation with First Amendment lawyers and news organization executives, formalize a list of “Media Ground Rules for Guantánamo Bay, Cuba.”

Today, these ground rules include a ban on three kinds of photographs: those that might reveal the identities of either prisoners or military personnel who guard them; pictures that provide panoramic views of access roads or security borders; and pictures of security cameras, fences, or locks. All photographers have to submit their photographs and videos for security review, with censors retaining the right to destroy any and all images they find unacceptable. The DoD also bans smartphones because they can upload photos directly to the cloud and bypass the review process.

Under these obstructive conditions, journalists, photographers, and artists’ efforts to report on Guantánamo often become as much a story of censorship as about the largely-invisible detainees. Eugene Richards’ 2013 Time photo-essay, much like the pictures taken by AP photographer Brennan Linsley and so many others, features plenty of barbed-wiring fencing, but only the shadows of men whose faces can’t be shown, and cell blocks without people.

The photo-essay produced by Mills and Times reporter Carol Rosenberg features some of those same photographic strategies. From start to finish, the essay includes images of incarceration that passed muster even as they call attention to the military’s refusal to let us see.

In this photo taken from ground level, a bright blue sky backlights the panoptical gaze from the opaque windows of the guard tower looming over the scene. In the center of the image, barbed wire on top of a chain link fence pulls our eye toward an American flag mounted on the stone structure, connecting patriotism to surveillance and detention. The caption notes that journalists were allowed only a few hours of the four-day visit at the Detention Center Zone. Echoing the obstacles implied in the caption, the tower’s imposing presence exemplifies the barriers preventing us from seeing the “secretive world” of Guantánamo Bay.

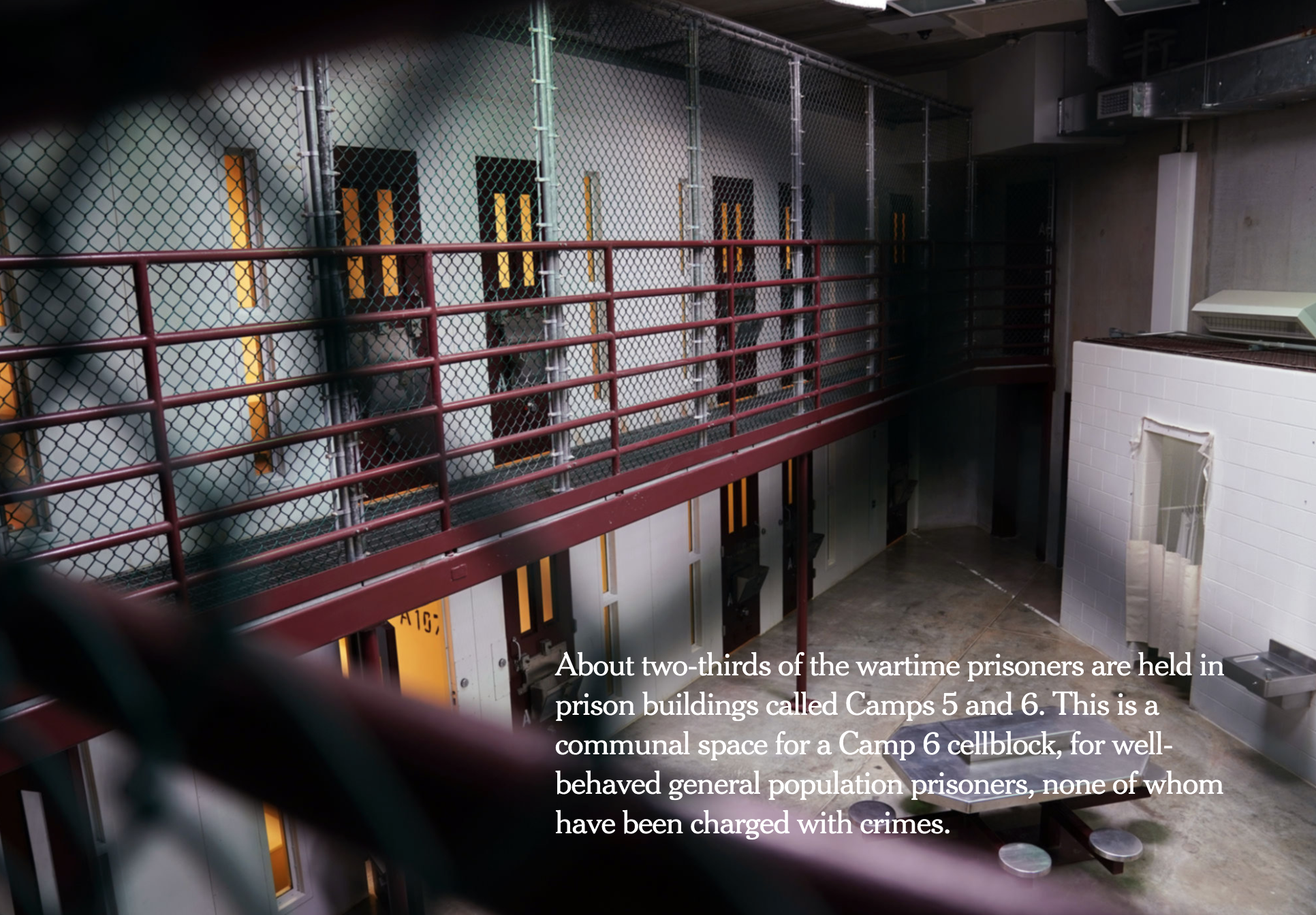

Another common photographic strategy that maneuvers within and pushes against military censorship is to show the interior scene of a cell block without prisoners. In the Times essay, for instance, an empty table and benches on the first floor of a two-story block reflect the meager communal space provided for “well-behaved prisoners.” Hauntingly empty, we know nothing of what constitutes good behavior for these prisoners we do not, and cannot, see.

Admittedly, there is a risk that by highlighting acts of censorship we might lose sight of the story itself — the abusive conditions and human rights violations of prisoners held at Guantánamo for over a decade without charges and without trial. These are men whose bodies often are controlled to the point of routine force feedings in the wake of the long-term hunger strikes begun in 2005.

But just as Rebecca Adelman powerfully reminds us to ask, what would we know about these men if we could see them? Less about them than about ourselves, she argues, because the stories that have circulated in the media and by politicians during the War on Terror have projected imaginary characteristics onto these detainees. So powerful are these stereotypes that it makes it almost impossible for us to see the prisoners as discrete political subjects.

Photographer Debi Cornwall confronted this dilemma head-on in her book on Guantánamo by including portraits of released detainees, but with their faces all turned away from the camera’s gaze. Echoing DoD’s “Media Ground Rules,” Cornwall turns this refusal to gaze around, lest we presume that by seeing their faces we can ever know them or know what they went through. Seen this way, the absence of detainees from view in most coverage of Guantánamo has an ethical benefit, since they cannot give (or deny) consent to having their pictures taken or circulated.

A waving plastic Ronald McDonald statue behind a fence is one of the only full-frontal portraits in the Times essay. Of the many people we cannot see, the caption explains, photographers are not allowed to photograph Jamaican and Filipino guest workers who comprise about one-third of base residents and who are the “stalwarts of the base’s service sector.” Instead, we have a portrait of this iconic figure of American consumer culture; one can but presume that Mills, Rosenberg, and the Times editors intended this as an ironic statement about how secrecy and captivity at Guantánamo undermine American ideals.

Across fourteen years of detention at Guantánamo, Americans seem to have grown complacent about the situation there. Transparency cannot resolve all the issues associated with media coverage of this facility, but without it, journalists face ever-increasing obstacles to reporting on human rights abuses. Still, the repetition of content across a host of photographic projects, including most recently this New York Times photo-essay, should sound the alarm bells. Despite constitutional protections that include freedom of the press, censorship at Guantánamo persists unabated. And as long as that censorship remains, stories containing by-now familiar pictures of the prison slip further and further from the front page.

— Wendy Kozol

Photos: Doug Mills/The New York Times. Caption 1: Nearly two decades after it was opened to house terrorism suspects and enemy fighters picked up on the battlefield in Afghanistan, the military prison at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, remains shrouded in secrecy. Image by Doug Mills. Cuba, 2019. Caption 2: To document this trip, the photographer Doug Mills presented his photos for review. The military censors images it believes could threaten security, like showing locks and cameras, or impinge on the privacy of detainees. Mr. Mills had to delete as many as 40 percent of his images from the detention center. Caption 2: During the four-day visit, only a few hours were allocated to the sprawling Detention Center Zone, whose staff of 2,000 United States military personnel and civilians oversees the remaining 40 detainees, just one of whom has been convicted of a war crime. Caption 3: About two-thirds of the wartime prisoners are held in prison buildings called Camps 5 and 6. This is a communal space for a Camp 6 cellblock, for well-behaved general population prisoners, none of whom have been charged with crimes. Caption 4: About one-third of the base residents are Jamaican and Filipino guest workers, but the military generally forbids photography of them. They are stalwarts of the base’s service sector, for example working at the base McDonald’s.

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus