Notes

Photo: Samuel Corum/Getty Images Caption: The bust of U.S. President Zachary Taylor is covered with plastic after blood was smeared on it when a pro-Trump mob broke into the U.S. Capitol building on January 7, 2021 in Washington, DC. Following a rally yesterday with President Donald Trump on the National Mall, a pro-Trump mob stormed and broke into the U.S. Capitol building causing a Joint Session of Congress to delay the certification of President-elect Joe Biden’s victory over President Trump.

Capitol Artwork a Symbolic Participant in Trump White Supremacist Riot

While the rioters who invaded the Capitol amplified the nation’s history of white supremacy, that history was already hanging on the walls behind them.

By Cara Finnegan

The U.S. Capitol is as much a museum of the history of the nation as it is a site of contemporary political power. As a result, it’s a complex memory space. Just how complex became evident after the events of January 6. In the days since, the extent of the physical destruction has become clearer, but sorting through claims of symbolic violation is a bit more tricky.

Much has been made of the dramatic visual contrasts between the hallowed halls of this secularly sacred space and the mob that willfully desecrated (and yes, even defecated in) them. But ironies lurk within the visual contrasts so carefully and courageously captured by photojournalists.

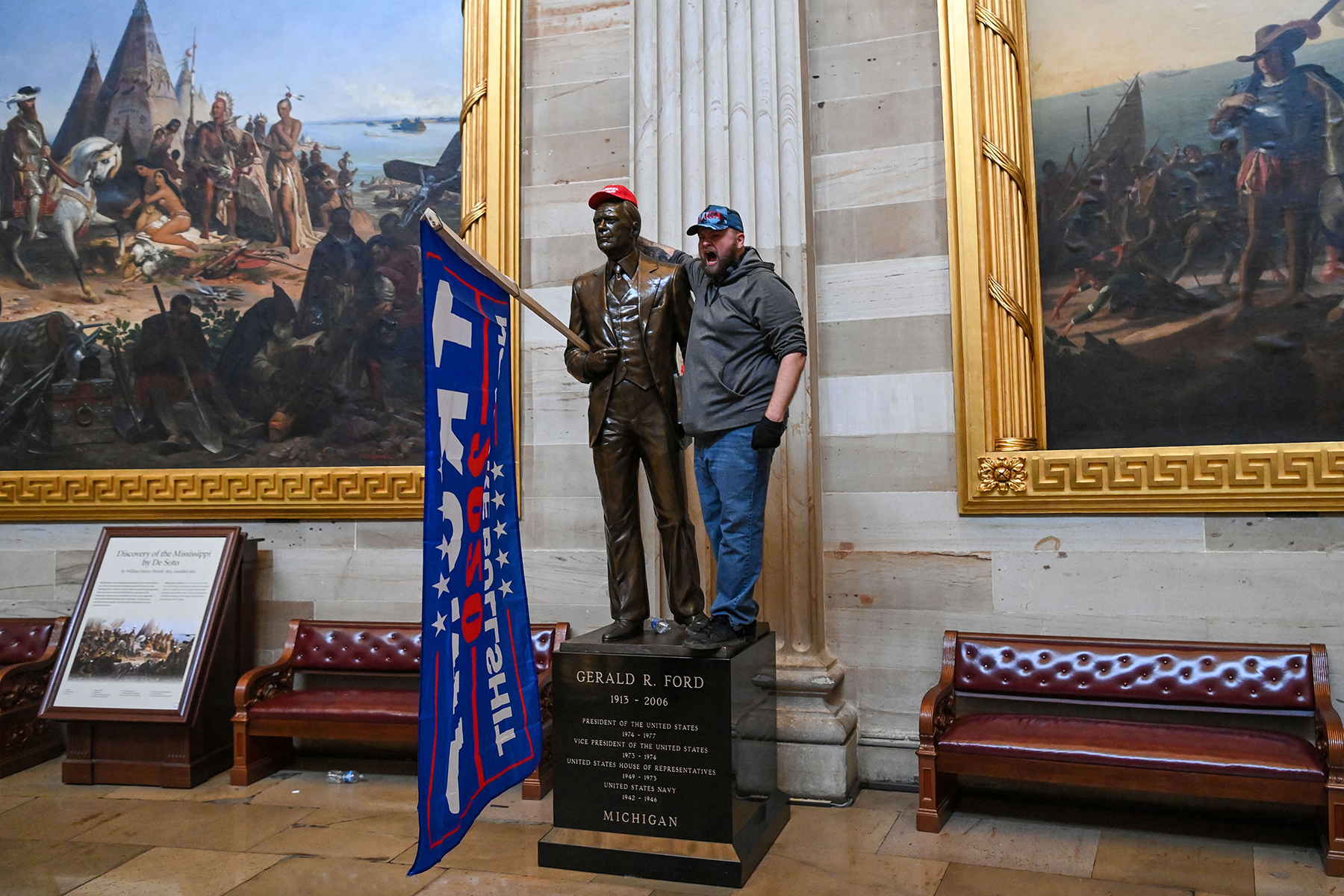

Caption: Supporters of US President Donald Trump enter the US Capitol's Rotunda on January 6, 2021, in Washington, DC. - Demonstrators breeched security and entered the Capitol as Congress debated the a 2020 presidential election Electoral Vote Certification.

Saul Loeb made this image of the statue of Gerald Ford as rioters roamed the Capitol Rotunda, a space usually teeming with tourists and school groups. Members of the mob also posed for photos with statues of Ronald Reagan and Dwight Eisenhower, so maybe they were just on the lookout for Republican heroes. Yet while Ford is the man who pardoned Nixon (setting a nice precedent for their guy), it’s still disconcerting to see him cosplaying MAGA and being made to wave a flag that reads “Trump 2020 NO MORE BULLSHIT.” Ford was not, in politics or disposition, MAGA material. But the man who has put himself on a pedestal with Ford has taken care of that. In a literal performance of the “there, I fixed it for you” meme, Ford is remade as a smiling friend of the mob.

But Loeb’s photo also makes clear that this appropriation of Ford occurred in the Capitol Rotunda, a space dominated by a series of narrative paintings that tell a familiar, yet distorted and incomplete, story about the origins of the nation.

The two paintings seen in the background of this photo, of De Soto “discovering” the Mississippi River, on the left, and the landing of Columbus, on the right, are emblematic of that partial history. They and others like them were commissioned and installed during the mid-19th century, at a time when the U.S. government was aggressively working to expand the boundaries of the nation and the question of slavery dominated Congressional debate. Ultimately, these paintings’ colonialist versions of “freedom” and “discovery” are just as implicated in the MAGA narrative as is the hat incongruously placed on Ford’s head. (Watch this Chatting The Pictures discussion of Trump’s bizarre Fourth of July visit to Mount Rushmore for more evidence of this connection.)

Caption: A supporter of President Trump carries a Confederate battle flag on the second floor of the U.S. Capitol near the entrance to the Senate after breaching security defenses, in Washington, January 6.

This widely circulated photograph also vibrates with references to history.

The initial visual contrast, of course, is the jarring introduction of the Confederate flag into the halls of the Capitol, where it flew freely during the insurrection. But Theiler’s photo also captures other juxtapositions. As historians quickly noted, the two portraits on the wall tell a story of their own. The image on the left is a portrait of John C. Calhoun, Vice President and Senator from South Carolina, emphatic supporter of slavery and states’ rights. The portrait on the right depicts Senator Charles Sumner from Massachusetts, who in 1856 was beaten on the floor of the Senate by South Carolina congressman Preston Brooks after Sumner delivered an anti-slavery speech.

The juxtaposition of the portraits, surely not lost on the Capitol curators who placed them together in that space, brings to life the charged debates of the era. And Calhoun himself is hardly a fuzzy figure from a distant American past. He has become newly relevant in an era where Americans are revisiting the ways we remember and memorialize. For example, after many years of debate, in May 2020 the City of Minneapolis renamed Lake Calhoun, which now is officially known by its historic Dakota name, Bde Maka Ska. In June, amid summer racial justice protests, a statue of Calhoun in downtown Charleston was removed, and Clemson University voted to remove Calhoun’s name from its Honors College.

While rioters with a Confederate flag amplify the nation’s history of white supremacy, that history already hangs on the wall behind them.

Caption: A statue was defaced during the riot on January 6 at the U.S. Capitol.

This final image of a bloodied Zachary Taylor in Statuary Hall, like the one wrapped in plastic above, punctuates my overall point: the artwork in the U.S. Capitol became an unwitting, but not always ill-suited, symbolic participant in the mob action incited by the president on January 6. Even if the plastic bag was applied by the cleaning crew, it still makes for a haunting news photo for the sense that the former president has been suffocated.

As jarring as it is to see the nation’s so-called sacred spaces “desecrated” — like this image of Taylor, literally punched in the face — looking carefully and asking questions about whose spaces, whose images, and whose histories we commemorate is more important than ever.

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus