Notes

War Enabling: Duckrabbit vs. Haviv and VII in a Larger Context

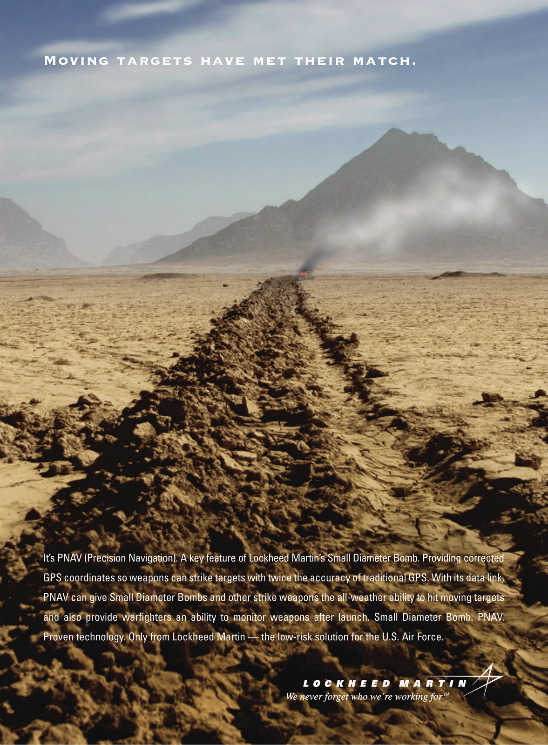

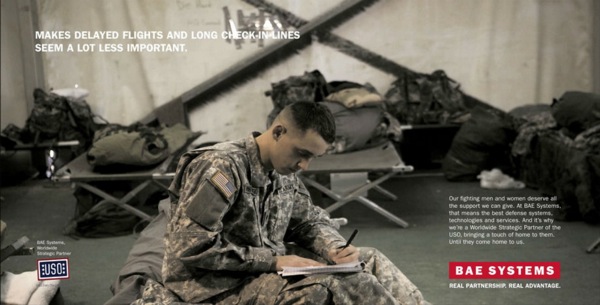

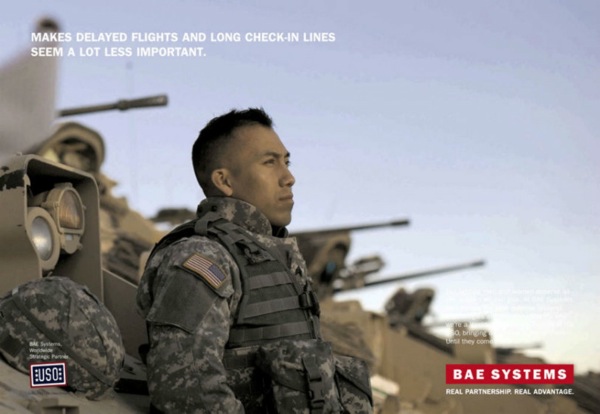

This week, photo-blogger Benjamin Chesterton took photographer Ron Haviv, and his agency, VII, to task for commercial photographs Ron did for arms manufacturers Lockheed Martin and BAE Systems. Benjamin accused both of hypocrisy given the firm’s reputation and pride for its humanistic conflict work.

To the extent this debate fixes around who is more justified — if Chesterton is, and Haviv is a sellout; or Haviv is, and there’s a clean line to be drawn between the types of work — we will have missed an opportunity to look at larger issues at play. Simply put, moral compromise is rife when it comes to war and photojournalism.

Starting with Ron, I believe we still see that compromising going on in his explanation/rebuttal, especially the way he relates how his image, sold to Lockheed Martin, has been appropriated. Ron writes that all he did was sell “a stock photo of tracks in the desert.” And from there:

“My commercial agent sold the landscape image as stock to Lockheed Martin, which exercised its right to add smoke and text.”

Ron doesn’t tell us if the “landscape” image was shot in Afghanistan or California, or if the tire tracks are from a tank or a tractor, but I can’t imagine he felt all that clean when the company reworked the photo into “the end of the road” for something, or imaginably, somebody (or bodies) getting incinerated by a Lockheed PNAV SDB.

The same can be said for the BAE ads where these photos, ostensibly for the “good guy” support organization, the USO, all-of-a-sudden get re-deployed by the arms contractor. In this case, Ron’s “support the troops” photography is used to confer a nobility on the soldiers (and BAE) in what also reads like some kind of emotional respite and deep reflective vacation from the hassles of civilian life and travel.

But does it really stop there? Frankly, it’s hard to see war photography these days as anything but a moral compromise across the board.

For example, how is the embedding program anything else but a moral compromise? How are those emotional bonds, and the natural empathy that develops between soldiers and photojournalists anything but a moral compromise? How is photo story after photo story of medevac missions — dramatic and heroic reportage facilitated in lieu of imagery that delineates an actual war front or the battle on the ground — something else beyond moral compromise? And, regarding the photographer, Noor-Eldeen, who was killed by the attack helicopter, why shouldn’t someone like Eric Draper be shunned because, as Bush’s White House photographer, he burnished the presentation of the person more responsible for Noor-Eldeen’s death than anyone at Lockheed?

I agree with Joerg that you don’t work with arms contractors if you’re a compassionate war photographer. But are there larger conclusions to be drawn that allow us to build on duckrabbit’s throw down in a more constructive way?

I imagine photo agencies and their individual members, especially the non-corporate ones, can formally agree to refuse any commercial assignments from arms manufacturers if that agency is going to be involved in conflict coverage. Perhaps restrictions, or at least “right of refusal” on the adaptation/doctoring of the photo are in order also? On a broader scale, though, what about a more concerted effort by the photo community and its organizations to advocate for negotiated rules of media-military engagement, and an oversight process aimed toward the overhaul and/or creation of alternatives to the embedding system? What about a more concerted call for access to more stealth operations, including special ops and cyber-warfare? How about calling for greater access and disclosure regarding the function and scale of the military’s internal media/propaganda operations? How about putting pressure on universities, such as Syracuse, to drop DoD funded military photojournalism (i.e. propaganda) training programs? As the visibility of photos, and photographers, and the risk to photographers goes up, why not the level of advocacy, too?

In a militaristic society, especially post 9/11, where war is huge business and war makes great politics (the Obama’s campaigning hard around military installations and doing one base visit after another), we’d do better to admit moral compromise is everywhere. And with that, rather than picking each other apart, perhaps we (shooters and writers) might actually pick some battles together.

(If you’re in or near Brooklyn on June 23rd, I’ll be speaking at the Photoville photo festival in Dumbo at 4:45 pm on “The State of the News Photo.” Hope you can make it.)

(photos: Ron Haviv)

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus