Notes

We Are All Bystanders: 18 Visual Scholars Reflect on Previously Unseen JFK Assassination Photographs – #3

This is the last of three posts dedicated to the 50th anniversary of the Kennedy assassination. We invited a group of distinguished visual scholars to provide us with a brief response to photographs from November 1963. The images come from this unique set of photographs published at the New Yorker PhotoBooth three weeks ago. The anonymous photos, from the International Center for Photography, were published for the first time. Here is a link to the whole series. You can find credits for each scholar at the bottom of each post. Click on each photo for full size.

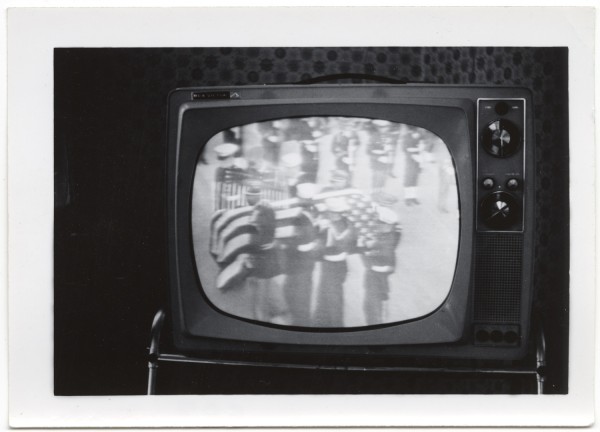

Television image of John F. Kennedy’s flag-covered casket. Unidentified photographer, November 24, 1963.

Wendy Kozol

Someone stood in their living room pointing their camera at the television in order to take a photograph of the live coverage of Kennedy’s funeral. The photographer navigates several layers of mediation to get a clear picture of marines carrying the flag-draped coffin. Slightly off center, the television sits on a metal stand with wallpaper barely visible in the background. What a distinctive act, in this nascent moment of television news, for this anonymous photographer to stand in a living room and point a camera at a tv set. Like selfies today, aesthetics matter little as the picture locates the funeral coverage within a domestic space in order to proclaim the photographer’s presence at this historic event. If this seems naïve or quaint in comparison to social media and personal photography today, this “mediation of mediation” speaks to the myriad ways in which people have long navigated personal and public identities through available visual technologies.

Christa Olson

“If you don’t come to Dealey Plaza this year, then the assassination is very much as it was 25 years ago: Reality framed by a television set.”

– Judd Rose, Nightline, November 22, 1988

You already know the cliché: baby boomers remember exactly where they were when they heard the news of President Kennedy’s assassination (my mom was in band practice in West Virginia, my dad in Algebra class in Iowa). Those located experiences brought the assassination close to home. And it came even closer in subsequent days when Americans were a nation brought together by viewing–96% of U.S. households tuned in to television coverage that weekend. Our national memory of the assassination today is a tangle of those personal stories and common viewership.

The fact that my parents have stories of the assassination, not to mention that they are remarkably similar, speaks to how overlapped public and personal memory are. For me, this picture encapsulates that too. The photograph treats a television image as if it were a family snapshot. But, unlike these other three television stills which frame out the television, this photograph draws attention to it. Looking at it today, we see an individual photographer claiming a place within the story of the assassination just as my parents did with their classroom memories. Though the photographer was most emphatically not there at the funeral (because s/he was there in the modest living room that surrounds the television), s/he participates in the distant event by photographing both it and the television that carried it. Like the reams of letters that viewers wrote to network television hosts after the assassination, then, this photograph makes visible the mass mediated, widely shared, yet profoundly private experience of remembering together.

Jon Simons

An anonymous photo of a TV, whose screen shows JFK’s casket flanked by military pall-bearers. The photographer had the skill to capture the image on the screen rather than reflected flash light, the background of wallpaper indicating that the photo was taken inside, perhaps in a living room. The picture is a picture about pictures, or a metapicture, as visual cultural scholar W.J.T. Mitchell would call it. The photograph shows that the real event is not given to the still camera, but to the TV as an apparatus that brings a distant event right into the home, live. It is a record, from a time before the VCR, of a dramatic, awful, event, but also one of those late twentieth century phenomena, a media event in which “history” is broadcast live and the audience, the public, is transformed as it watches. The media event, though, also mediates a traumatic event, a rupture in the flow of American history, an interruption to which we return, as we do to all traumatic moments, belatedly, because the event could not be assimilated into experience as it happened. The photograph is thus a metapicture in a different sense too, as it shows the role of photography in establishing a memory of the event. The TV footage flows forwards in time; as John Berger reminds us, the photo is retrospective, the material of memory.

Television image of John F. Kennedy’s funeral procession by caisson. Unidentified photographer, November 25, 1963.

Anne Demo

Just as the presidential debate between John F. Kennedy and Richard M. Nixon marked a turning point in the history of television and presidential campaigns, the Kennedy’s funeral established key norms for the televised spectacle that would come to dominate coverage of national traumas in subsequent decades. It is difficult to examine the “Television image of John F. Kennedy’s flag-covered casket” either denotatively or connotatively as the image now functions almost exclusively as a symbol of the televised spectacle. In comparison, the “Television image of Jacqueline Kennedy and Caroline Kennedy during John F. Kennedy’s funeral proceedings” from yesterday’s post maintains a denotative and connotative pull through the image’s spatial organization. The divergent gazes signify the confusion and isolation experienced in the aftermath of tragedy whereas the extreme cropping anticipates the voyeuristic appetite and erosion of privacy that has come to define the political spectacle in our own time.

Brian L. Ott

In his 2010 book, The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains, Nicolas Carr makes the sweeping claim that “The Web is a technology of forgetfulness” (p. 193). Carr, a self-described (technological) determinist, bases his claim on the idea that the technology of the internet prevents short-term memories from being converted into long-term memories. While his discussion focuses predominantly on personal memory, Carr recognizes that the ubiquity of digital technologies (along with their endless (re)circulation of information) in our lives today has important implications for cultural memory as well. If Carr is correct that the “Web is a technology of forgetfulness,” and I think he is, then the rise of the digital archive raises serious questions about our capacity to form cultural memories in the digital era.

Part of the difficulty, I would like to suggest, is that digital archives are disembodied and, therefore, not repositories of memory at all (only data). What is lost in the transformation of cultural memory into the digital archive is, among other things, the decidedly affective dimension of memory. Without this dimension, the digital archive is little more than a storehouse of radically disembodied data. Some will, no doubt, counter that the digitized (and print) images documenting the dramatic events of November 22, 1963 elicit powerful affects all on their own (a claim with which I do not disagree). But the affect generated by the aesthetic qualities of these images and the affect associated with JFK’s assassination are not the same thing and, thus, neither are the cultural memories they rhetorically promote. Critics would be well advised, then, to attend carefully to the social and political implications of those differences, for such images may play a greater role in the erasure (or, at least, the remaking) of cultural memory surrounding JFK than in its preservation.

Television image of Lee Harvey Oswald taken into custody for alleged assassination of John F. Kennedy. Unidentified photographer, November 22, 1963.

Michael Butterworth

Shuffling through the images from “A Bystander’s View of History,” I struggled to generate my own interpretation of them. I was born in 1971 and, although I know much about the historic events connected to JFK’s presidency and assassination, I recognize that much of that knowledge is the product of others’ accounts, especially those circulated in popular media. How much, then, am I dependent on a generational reading of these photographs? I certainly can visualize prominent themes–Kennedy’s youth and charisma, the public’s enthusiasm for the idealism he represented, the presumption that the United States in 1960 was an innocent land yet to fall victim to the cynicism brought on by the twin scandals of Watergate and a failed war in Vietnam (“Where have you gone, Joe DiMaggio…?”). Nevertheless, these are the readings I know I am supposed to have, filtered through decades of nostalgic recollections of the Kennedy years as well as my own lifetime’s parallel experiences–the exuberance of a Barack Obama candidacy; the national tragedy of 9/11. In short, these images remind me that a narrative about JFK has already been constituted rhetorically, through the years of remembrances and memorializations. I want these images to speak to me; but I fear I have already heard what they have to say.

Robert Hariman

The strange combination of guilt and innocence refuses to go away. Guilt, because A Bystander’s View of History implicates all viewers in the “bystander behavior” that not much later became a social fact. We watch the murder without acting, not only too late but psychologically incapable of intervening. Politics was a charmed circle containing its own serpents, with the public relegated to permanent complicity in crimes beyond its control. Innocence, because the worn prints, faded colors, and grainy snapshots (early screen grabs) of black and white television sets reassure us that everything was different then, simple images from a simple time when idealism meant something, back in the past that is the most evident feature of every one of these photographs. Indeed, the material images really aren’t photographs anymore: they have been transmuted into relics. Like the saint’s bone or tuft of hair, the frayed prints promise immanent connection to spiritual power—the power of a lost world that never was.

See the entire series here: Visual Scholars Analyze JFK Assassination Photos

————-

Wendy Kozol is Professor and Program Director of Comparative American Studies, Oberlin College.

Christa J. Olson, Assistant Professor of Composition & Rhetoric at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her forthcoming book is: Constitutive Visions: Indigeneity and Commonplaces of National Identity in Republican Ecuador

Jon Simons is Associate Professor of Communication and Culture at Indiana University, Bloomington. His current research project and blog is about Israeli peace imagery.

Anne Demo is Associate Professor, Department of Communication and Rhetorical Studies and School of Art and Design, Syracuse University. Her edited volume with Bradford Vivian, Rhetoric, Remembrance, and Visual Form: Sighting Memory, was just made available in paperback.

Brian L. Ott is Associate Associate and Associate Chair, Department of Communication, University of Colorado, Denver.

Michael L. Butterworth is Director and Associate Professor, School of Communication Studies, Ohio University.

Robert Hariman is Professor, Department of Communication Studies, Northwestern University. He’s co-author, with John Louis Lucaites, of the related blog and book “No Caption Needed: Iconic Photographs, Public Culture, and Liberal Democracy,”and he’s a contributor to this site.

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus