Notes

Take It Down (LEAVE IT UP): On Congress Tiff over Ferguson Painting

Over the last couple days, a near-literal tug-of-war has been taking place in the Cannon Tunnel of the U.S. Capitol building. Three times (at last count), Republican members of Congress have removed a painting hanging in the annual U.S Congressional Art Competition show. Three times (at last count), Representative William Lacy Clay (D-MO) has replaced the painting.

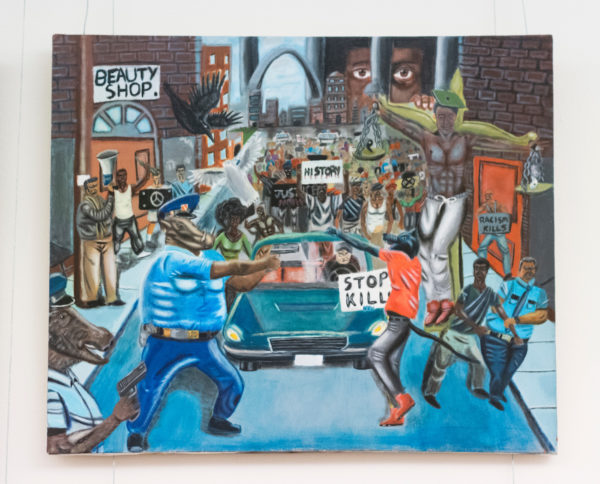

The painting is an acrylic on canvas by David Pulphus, a recent high school graduate from Representative Clay’s district—which includes Ferguson, MO. It shows an anti-racism protest. In the center foreground, two police officers with drawn guns approach a protestor with his arm extended in defiance, fist raised. While the many other figures in the painting are humans—including another protestor and police officer in the right foreground—the three central figures are all animals. This is the primary point of contention. One police officer is a barrel-chested wild boar and the other is more ambiguous, perhaps another boar, perhaps a donkey (Politico sees a horse). The protestor has the face and tail of a black wolf or dog. Local law enforcement officers complained about the painting, saying it showed disrespect for police officers, and Representative Duncan Hunter (R-CA) acted on his own last Friday to remove it.

Representative Clay, along with two other members of the Congressional Black Caucus, Representative Cedric Richmond (D-LA) and Representative Alma Adams (D-NC), held an event on Tuesday to re-hang the painting. That afternoon, Representative Doug Lamborn (R-CO) removed the painting again, and Clay hung it again. Tuesday evening, Representatives Brian Babin (R-TX) and Dana Rohrabacher (R-CA) took down the painting. Clay returned it. Politico reports that Paul Ryan himself has weighed in and promised that the painting will not remain, though he prefers its removal follow official protocol.

Tempting as it is, I am not going to comment directly on the painting itself and whether it ought to remain in the Cannon tunnel. Doing so would obscure three other points about this controversy—and about visual politics—that merit our attention. I offer those points here, in brief:

- Pictures gain power when they are given power, and Representatives on both sides of this issue seem to both know that and forget it.

Photographs of the Congressional Art show suggest that Pulphus’s painting was hung among many others in the tunnel connecting the Cannon Office Building with the Capitol itself. While its bright colors and controversial subject would make it stand out, it was not originally positioned to call much attention to itself. Indeed, the first complaints about the painting by law enforcement and Representatives came not because they themselves had noticed the painting but because Independent Journal Review posted a story about it. This tug-of-war changed that. Representatives Hunter, Clay, Richmond, Adams, Lambor, Babin, and Rohrabacher have ensured that Pulphus’s painting will be widely seen and debated.

On the one hand, this tendency to lend the painting power through circulation seems unconscious. Statements against the painting especially presume it has power by its very existence. On the other hand, it is clear that the spectacle serves a purpose here. Clay, Richmond, and Adams may have avoided directly endorsing the subject of the painting, but their ceremonious (and media-invited) replacement of the painting provides visual evidence of both their political stance against the disproportionate violence that people of color face from the police and their shared commitment to defending the rights of their constituents. It does not take three people to re-hang a painting (in fact it makes it more difficult), but photographs of three members of the Congressional Black Caucus putting the painting back in place quite defiantly lend both the painting and their act a heft they might otherwise lack.

- The painting’s own details do not lend themselves easily to the “cops-as-pigs” stereotype, but the stereotype itself is clearly determining how people view the painting.

CNN says that Pulphus’s painting “depicts some police officers as pigs.” This is a stretch in at least two ways. First, “some” generally suggests more than one. Of the two animal-officers in the painting, however, only one is unambiguously porcine. Second, while wild boars are of the same general species as domesticated pigs, they aren’t the picture that usually comes to mind when someone refers derisively to police officers as “pigs.” In the quick and highly scientific Google image search I conducted, all but one of the images in which a police officer is given a boar’s face are pictures of Pulphus’s painting. Pulphus was likely riffing on the old insult when he painted his police officer with a long snout and tusks, but it is still worth noting how quickly the painting became a case of “pigs.” I am always fascinated by the resilience of visual assumptions, and this case stands out as a powerful example. This painting becomes about insulting depictions of police officers as pigs because pigs are the animals we associate with police officers and two of the police officers in the painting are depicted as animals. The visual complexity of Pulphus’s actual painting fades into the background when confronted with the juggernaut of visual habit.

- This controversy is straight out of the 1990s culture wars: a battle over morality, decency, and free speech updated only by its focus on racism and police violence rather than sexuality.

- Reps Rohrabacher/Babin take pigs/police painting back to Rep Clay’s office. pic.twitter.com/VitINb0qJ2

— Chad Pergram (@ChadPergram) January 10, 2017

Is this dispute over art a weird throwback to the culture wars or a sign of things to come? Or is it, perhaps, a reminder that the culture wars never left us in the first place? I have been wondering about the future of the NEH and NEA lately. Rep. Hunter’s moral indignation, so palpably visible in the photographs of him circulating alongside this story (see above), does not bode well for those agencies. If the members of the Congressional Black Caucus saw this painting as a symbol to rally around, Hunter and his Republican colleagues obviously see its removal in the same light: a stance for which there can be no conceivable downside. Pictures never stopped being a political battleground, but it’s been a little while since fine art faced direct attacks from the U.S. Capitol. We already know who stands where in these conflicts, but photos of Clay and colleagues replacing the painting while Hunter objects in the foreground certainly draw those lines starkly for anyone who has forgotten (or wasn’t around for the battles twenty years ago).

Whether Pulphus’s painting ultimately comes down or stays up, a few things have been clarified by this controversy: pictures still pose a threat to power (or at least the powerful perceive a threat); “free speech” is, and always has been, tenuous territory for the arts; and—most importantly—perspective always governs what we see and how we see it. Many of the images of Pulphus’s painting in circulation right now show a cropped version that makes the confrontation in the painting’s foreground into the whole picture. In the process, we lose the specificity of setting (the St. Louis Arch) and the haunted eyes that observe the whole scene from behind. “Untitled #1” becomes “Cops as Pigs,” and the Annual Congressional Art Show becomes an ideological tug-of-war.

— Christa Olson | @christajolson

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus