Notes

The Remarkable Scenes of the Women Facing Larry Nassar

“Leave your pain here and go out and do your magnificent things,” Judge Rosemarie Aquilina said to the 156 girls and women who confronted Larry Nassar at his sentencing hearing. The former Michigan State and USA Gymnastics doctor was sentenced to 175 years in prison for sexually assaulting over 160 people, mostly female athletes, under the guise of medical treatment. The judge gave the women the opportunity address Nassar directly – an opportunity few sexual abuse survivors are ever granted – many speaking publicly for the first time.

Two kinds of images stood out for me among the hundreds of pictures taken at the trial. First are the stills of women’s faces, laid bare for clicking cameras. These faces capture the whole register of emotions: grief, loss, anger, trauma, bewilderment, acceptance, anxiety, contempt, overcoming, forgiveness, rage.

It is not surprising these images move us: the face is a visual trope at the forefront of media and political spectacle. Claimed by diverse political agendas, it has become a primary signifier of social issues including war, natural disaster, crime or economic inequality. Like no other part of the human body, it is invested with powers of interpellation. It is a gateway to an encounter. It makes us respond.

Faces of women and girls in Nassar’s trial summon us as witnesses of a years-long abuse; they serve as criminal evidence. At the same time, perhaps more than words, photographed faces make us aware how sexual trauma can disintegrate one’s identity. These are not harmonious, composed faces. They are interrupted in their symmetry and composition through barely contained emotions.

Correspondingly, in Western art history, the face has served various roles: a promise of revelation of a true self, the site of individualization, a mask performed for viewers, the token of civil identity. The face overcome with feelings and distorted by anguish is a powerful motif from the ancient sculpture of Laocoön fighting snakes and Greek mosaics picturing Medusa, through Francis Bacon’s pope portraits, Edvard Munch’s Scream, or the woman in the Odessa Steps scene in Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin, to images of children from this horrific Aleppo broadcast on CNN. I am shaken by the faces of former patients of Nassar as they come undone. I find it hard to look too long.

There is another kind of image from the trial I found just as disquieting.

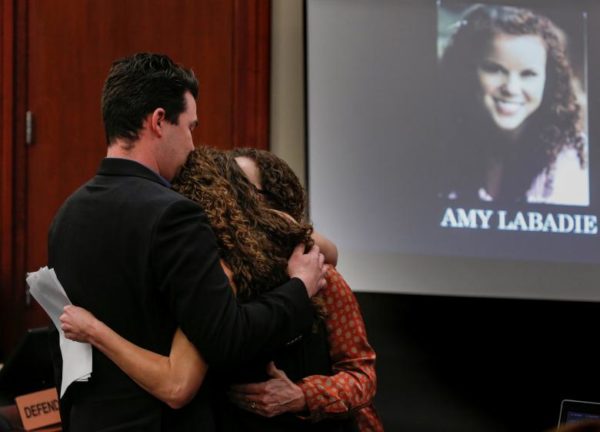

Many of the women are captured testifying in front of projected images of themselves at the time of their abuse. We see girls in gymnastics leotards holding trophies. We see school class portraits and family snapshots. On the surface, these young women seem to burst with pride, accomplishment, and happiness. Against the background of the courtroom, however, these projections become just that. They become questionable, ominous, fleeting.

The photographs within the photographs slide cast open the shutters between the past and present, the known and unknown, the safe and the deadly. Sexual trauma often lands in a representational void, but these images bring the un-picturable alongside the recognizable. Furthermore, the posed shots with costumes and trophies form a cruel parallel to Nassar’s Michigan State campus office. The space–dazzling patients and their parents, and disparaging doubts about his professionalism–is described in this Washington Post article as decorated floor-to-ceiling with signed pictures of Olympic stars (or framed bitterly by one of the women at the trial as “a shrine of his conquests”).

One of the functions of the camera is to hold aggressors and perpetrator accountable, to document social injustice and violence as a civil contract. Photographs of Eric Garner, Philando Castile, and Heather Heyer have captured that violence and brought it to the attention of a global audience. Images of fearless and resilient women at Nassar’s trial do not capture the act of violation itself, but rather its long-term effects, the lives that get derailed, the relationships that become broken, the bodies that turn precarious. As this view is revealed, it is up to us to ensure that those responsible for this violation and its silent bystanders no longer escape the frame.

-Marta Zarzycka

All photos: Brendan McDermid/ Reuters Photo 1: Victim Mattie Larson speaks.; Photo 2: Wednesday, January 17, 2018 Tiffany Thomas Lopez, a former member of USA softball team: “I imagine hitting you if I ever had the opportunity to see you again. Instead, I will allow my thoughts and my feelings to hit your heart. You and your actions have walked with me every step of the way since leaving Michigan State University. Since you’ve decided to tell the truth about sexually assaulting an army of young women, I’m choosing to stand tall with them and fight back. The army you chose in the late ’90s to silence me, to dismiss me and my attempt at speaking the truth will not prevail over the army you created when violating us. We seek justice, we deserve justice and we will have it.”; Photo 3: Tuesday, January 16, 2018, Kyle Stephens said Larry Nassar, a family friend, began molesting her when she was 6 years old and her parents did not believe her when she told them. “You convinced my parents that I was a liar,” Stephens said. “Little girls don’t stay little forever,” she added. “They grow into strong women that return to destroy your world.” Once her father realized she was telling the truth, he took his own life, Stephens said.; Photo 4: Monday, January 22, 2018, Victim and former gymnast Whitney Mergens: “He believed he could relieve some back pain. With my mother in the room, he managed to slip his cold bare hands up my shorts and slid his fingers into the most personal area of my body. As he pushed I was in much discomfort. It felt like it would last forever. When it was over my 11-year-old innocent mind was oblivious to what had just happened. I knew it hurt, but he was the Olympic doctor, so I thought it must have helped.”; Photo 5: Victim Amy Labadie is comforted after speaking.

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus