Notes

Alan Chin on "the 9/11 Decade": Beyond Pushpins On A Calendar

September 11th, 2011: The 10th anniversary in Lower Manhattan.

I lived on the Lower East Side, but I slept through the impacts of the planes striking the Twin Towers, and only the ringing telephone woke me up. My brother in Michigan told me the news, and as he spoke I noticed that the normal sounds of street traffic were entirely gone, in their place the wail of sirens from emergency vehicles barreling downtown at very high speed. I switched on the TV, but couldn’t get any reception except for one faint, fuzzy station; the antenna had been on top of the World Trade Center. But that was enough.

Approximately 9:50 AM, September 11, 2001, on the corner of Church and Vesey Streets.

I rushed there and shot one roll of film before the South Tower exploded and I ran with a few police officers and firefighters into the basement of an office building, thinking that the tower might fall on top of us. When we emerged, the entire world had changed. My father, who knew I had gone to the scene, told me later that he was sure I was dead, watching the explosion from the coffee shop in Chinatown where he went for breakfast.

Approximately 11 AM, Broadway and Liberty Street.

Day became twilight gloom with smoke and ash, and for the next minutes and hours, I photographed on autopilot, unable to comprehend what had happened: One plane might be a horrific accident; two made no sense whatsoever.

I wasn’t the only one to revert to Cold War thinking, imagining a Soviet or Chinese pre-emptive strike even though the Soviet Union didn’t exist any more and China didn’t have the range. If World War Three was beginning, why wasn’t it nuclear, and all of us dead, or at least a steady stream of cruise missiles raining down upon the city? Only later in the day, as more details emerged, did I understand that I had just witnessed the most murderous, and hence effective, terrorist attack in history.

December 3, 2001: Northern Alliance soldiers wait in a snowstorm while their commanders negotiate the surrender of a group of Taliban still holding out in Balkh, Afghanistan.

Two months later, flying from JFK for Afghanistan, we could see Ground Zero still burning. It was a just war with universal outrage and support. The Uzbek navy ferried journalists across the Amu Darya River into northern Afghanistan, French paratroopers held the Mazar-i-sharif airfield, and small American teams were attached to each Northern Alliance unit. The conventional fighting was easy, and six thousand Taliban, Pakistanis and other foreigners of Al-Qaeda’s Islamist international brigade surrendered in Kunduz.

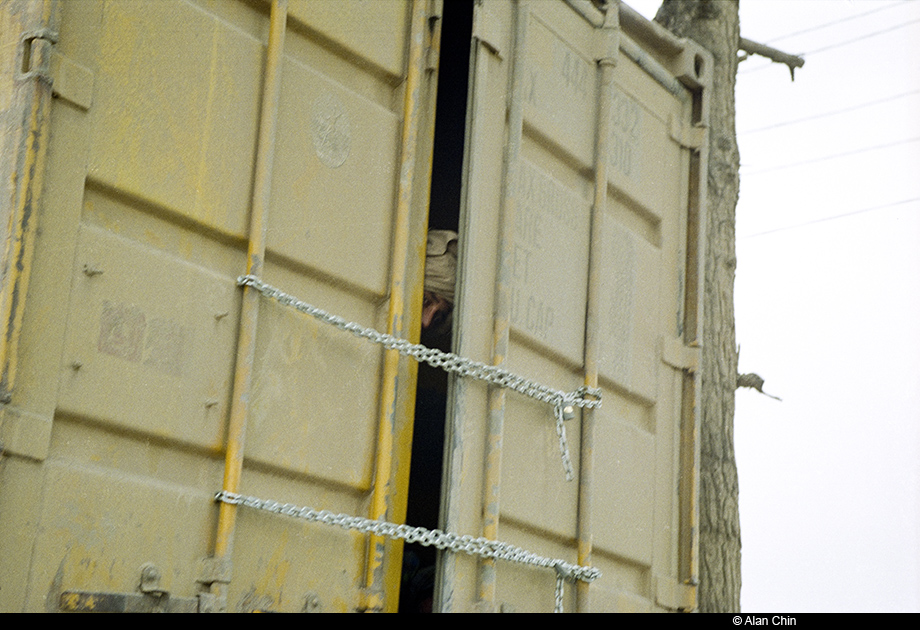

December 2, 2001: Thousands of Taliban soldiers were transported to a prison in Seberghan controlled by Northern Alliance general Abdul-Rashid Dostum. A prisoner looks out of the rear gate of a container truck as it enters the prison gates.

That was when I first began to realize that something was going seriously wrong in George W. Bush’s America, when at least a thousand of those prisoners died en route to prison, either suffocated in overcrowded trucks or helplessly massacred by vengeful Northern Alliance soldiers. The Geneva Convention was discarded, selected captives whisked away to Guantanamo Bay, and the United States was participating in or silently complicit to war crimes, under the exculpatory claim that we were fighting neither proper national states nor could our enemies then be considered simple, if arch, criminals. In that gray area, the laws of war and due process disappeared down a black hole.

But still, I could not come to those conclusions quickly. Bosnia and Rwanda had taught many of my generation to distrust pacifism and embrace humanitarian intervention. The America I grew up in had checked a previous era’s excesses by impeaching Nixon and welcoming cultural, racial, gender diversity in gradual, but meaningful ways. It was hard to believe and accept that with no evidence linking 9/11 to Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, President Bush would lead the nation into another, entirely unnecessary, war. Osama Bin Laden remained at large and the Taliban a threat.

March 30, 2003: The British Army attacking Basra, Iraq’s second largest city.

In my own life, my father died suddenly of a medical error in December 2002 and for me the rush to war receded into the background, a charade of brinkmanship. But like my personal tragedy, the invasion of Iraq was brutally, unequivocally real. No amount of over-thinking analysis could wish it away. Ascribing wisdom and complexity to our leaders did not endow them with such traits. I found myself once again covering an American war, and this time the breakdown of logic was glaring and obvious from the get-go. There were no weapons of mass destruction, and if Saddam Hussein’s totalitarian regime was truly on a different order of evil and murderousness — and, it was — then the only redemption for waging aggressive war to destroy it would be to quickly and decisively establish the conditions for civil society. But that could not be a lower priority on the war plan.

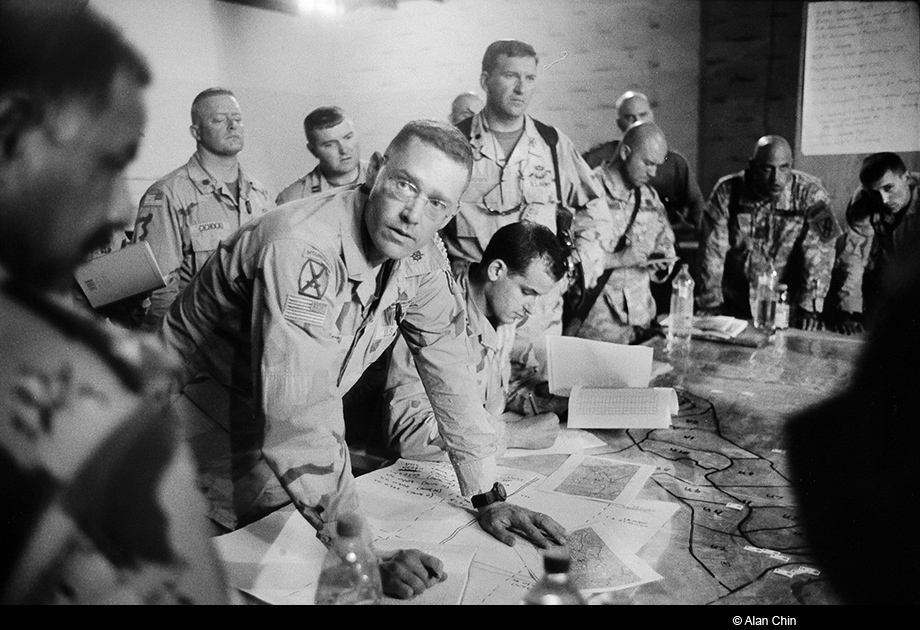

May 2005: American and Iraqi officers plan operations in the headquarters of an American brigade in Mahmudiyah south of Baghdad.

May 5, 2005: Remains of suicide bomber who killed 15 potential recruits awaiting entry to an Iraqi Army base, Baghdad, Iraq.

There is no need to repeat the litany of mistakes, miscalculations, and moral failures of America’s intervention in Iraq. On my second trip there in 2005, the sectarian civil war flared out of control with daily suicide bombings and heavy-handed American counter-insurgency in riposte. I came home and Hurricane Katrina unfolded from a terrible natural disaster into a collapsed response, starting with the incompetence of coping with the tens of thousands of survivors at the Superdome, and continuing through the protracted ordeal of FEMA trailer parks and a major American city still not entirely restored six years later.

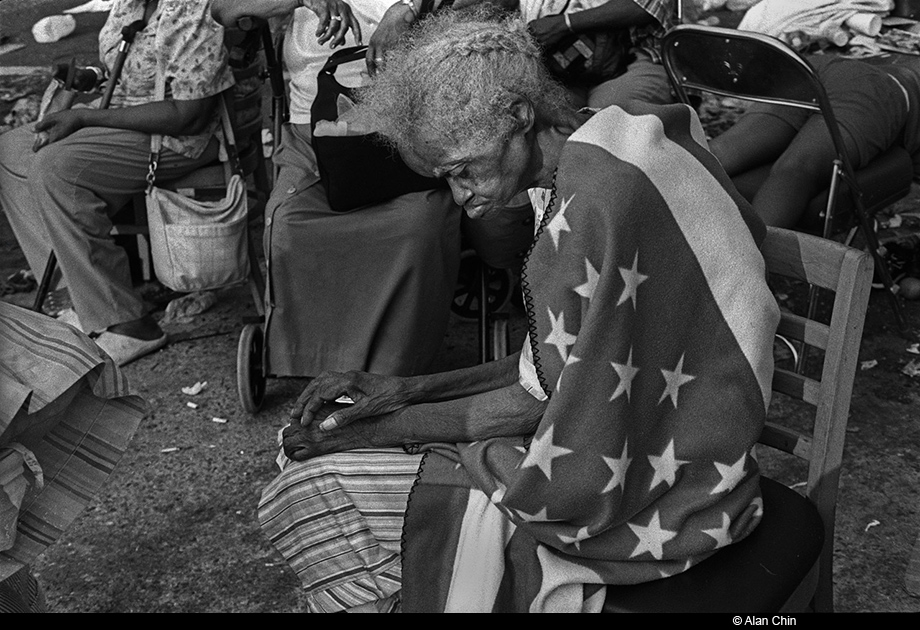

September 3, 2005: Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans. 84-year old Milvertha Hendricks wrapped in an American flag blanket after spending five days on the street at the Convention Center. She was not evacuated until the next day.

The same cultural and political attributes that led to quagmire in Afghanistan and Iraq were on display domestically in Louisiana. What I thought were much vaunted and celebrated American virtues of the can-do spirit, practicality, and civic idealism – virtues tarnished but not, I thought, vanquished by Vietnam or perennially cynical evocations of decline — turned out to be corroded and hollow indeed. Fear mongering, an exaggerated sense of entitlement, nativism, and naked partisan lust dominate the discourse, and the soaring idealism of the Obama campaign and presidency have turned out to be brittle and shallow in practice.

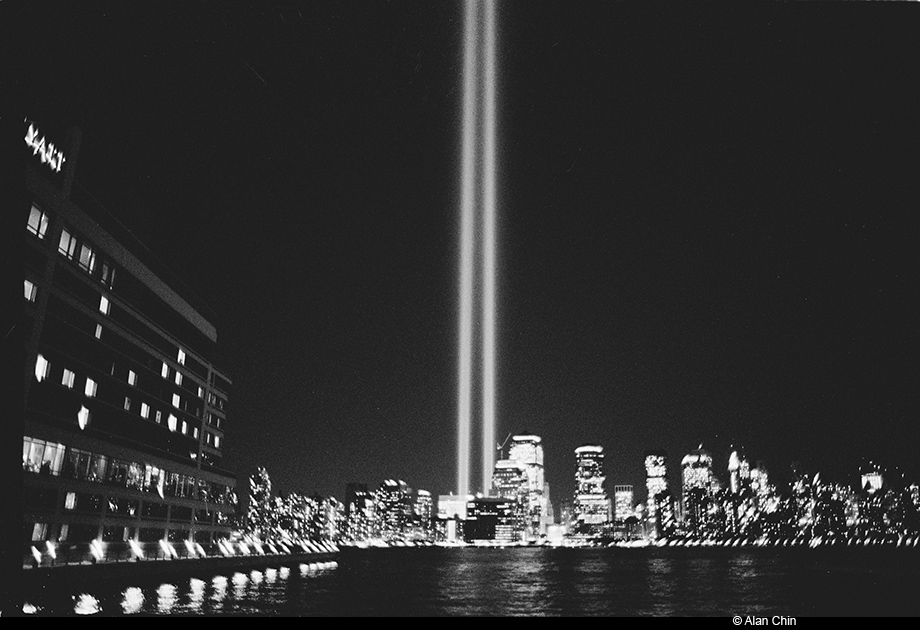

September 11, 2004: The Towers of Light memorial as seen from Jersey City, New Jersey.

Each September 11th at Ground Zero in Lower Manhattan, the ceremony expressing the heartfelt emotion of New Yorkers in mourning slowly became overshadowed by the World Trade Center site as a stage for chest-thumping and jingoistic expressions of nationalist excess. Last year, something that should never have become controversial became a contentious circus over the proposed construction of the Park 51 Islamic center. This devolution has been heartbreaking.

September 11, 2010: A crowd of several thousand right-wing protestors gathered against the planned Islamic Cultural Center on Park Place.

This year, the people of New York were encouraged to stay away. A massive security operation closed off much of Lower Manhattan. President Obama spoke, but essentially only to television cameras. In a different America, a million people might have come out to hear him and memorialize our dead, regardless of politics, class, or any other points of identification. Unity, contemplation, and grief are crucially appropriate at such a moment. Instead, the atmosphere was subdued in the extreme, with only tourists, the usual 9/11 conspiracy theorists, and local residents going about their daily business apart from the uniformed services and the families of the victims. Reserving the prime focus for their quiet and somber pain is absolutely right. We do some things well. But caving in to the fear of another attack, and allowing this universal tragedy to be appropriated by poisonous culture war speaks volumes to the cowardly and darker sides of the American character.

September 11th, 2011: The 10th anniversary in Lower Manhattan.

Though anniversaries may just be pushpins on a calendar, they are key markers of our individual and collective lives. The tenth has particular meaning by the measures through which we assess aging and change. My mother passed away several days ago after a long, terrible illness. I was thirty years old in 2001, I am forty now, and for me, September 11 will forever be book-ended by my parents: my father’s trepidation for me when he, unknowingly, had not long to live, and my mother’s death this past week. They may not be directly connected, but each of our experiences is entwined with the greater society to which we all belong.

The American Dream was not killed on September 11, 2001. As many said at the time, it was an opportunity, tragic and momentous, for the finer aspirations of American idealism to reemerge with passionate exceptionalism. Ten years later, those hopes lie shattered in the dust not of the towers, but of water-boarding, Predator drones, kill teams, rendition, and a national security state.

September 11, 2011: The USS New York, an amphibious assault ship built partially with the steel from the destroyed World Trade Center, anchored in the Hudson River next to Ground Zero.

September 11, 2011: The USS New York, an amphibious assault ship built partially with the steel from the destroyed World Trade Center, anchored in the Hudson River next to Ground Zero.

–Alan Chin

PHOTOGRAPHS by ALAN CHIN / facingchange.org

Minor text edit at 1318 EST, Sept. 12 2011

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus